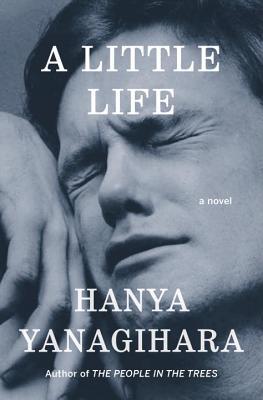

Review: Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life”

by Miles Raymer

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is a superlative novel in every respect. It is also the most emotionally challenging book I’ve ever read. Even after being forewarned by a friend, I was still completely unprepared for the onslaught of sensations and reactions this story elicited from me. Reading it was like being caught in a raging flood––one that I willingly immersed myself in over and over, even when it overwhelmed me to the point of tears or numbness.

I want to be clear at the outset: I would not recommend this book to most people. A Little Life looks humanity’s most depraved and evil actions straight in the eye, confronting the indelible effects of severe child abuse by forcing the reader to simulate trauma. This dynamic will be a dealbreaker for many readers, and would seem maudlin or sadistic if it weren’t so flawlessly executed. Yanagihara’s descriptive prose and depictions of memory are superb, as is her understanding of how people change or remain static over time.

A Little Life contains a huge cast of characters, all of whom are fascinating and worthwhile. The main story is about four friends who meet in college, but the majority of the book’s considerable pagecount is spent exploring the relationship between just two of them––Willem and Jude. Willem is an aspiring actor in New York City, while Jude is a brilliant young lawyer working for the US Attorney’s Office. Both men have come to New York from the American West, and both have lost their parents.

The similarities end there. While Willem had a typical if somewhat melancholy rural upbringing, Jude’s childhood was so difficult that he refuses to discuss it with anyone. Jude is also physically disabled; his legs and spine were mangled in a mysterious injury, causing him to regularly experience immobilizing episodes of intense pain. These debilitating problems barely scratch the surface of Jude’s overall physical and emotional damage. Despite his personal challenges, Jude proves himself to be a brilliant scholar, a prodigiously hard worker, and a good friend.

The reader is slowly introduced to the details of Jude’s past via flashbacks, but Jude refuses to share his story with his friends and loved ones for fear that they will see his “true nature” and reject him:

The person I was will always be the person I am, he realizes. The context may have changed: he may be in this apartment, and he may have this job that he enjoys and that pays him well, and he may have parents and friends he loves. He may be respected; in court, he may even be feared. But fundamentally, he is the same person, a person who inspires disgust, a person meant to be hated. (340)

This insidious form of self-loathing pervades Jude’s internal life and taints his interactions with the outside world. Jude is able to bestow generosity and love on others, but cannot view himself as someone who deserves to be loved in return.

Yanagihara’s excruciating descriptions of Jude’s abuse and its long term consequences are not cheap or lurid devices for generating sympathy, but rather essential mechanisms for rendering his behavior intelligible. By most external standards, Jude is incredibly selfish. He routinely puts himself at risk in ways that are codependent and even borderline abusive to those who love him. But Yanagihara is so adept at conveying Jude’s twisted logic that we can never bring ourselves to condemn him, even at his worst. A Little Life is therefore the epitome of an ethically complex narrative, one that seeks to explicate motivations without trying to justify them.

“Progress” or “recovery” are not active concepts in Jude’s world; most of the time, it’s all he can do to make it through the day. His anguish abates only intermittently, in times of intense happiness or exhilarating change. Financial success doesn’t help him heal, but it does provide the security he lacked as a child. Tragically, Jude leaves public service for more lucrative work in the private sector, not because he is amoral or power-hungry, but because he thinks wealth will be his only means of survival when his friends “inevitably” abandon him.

Although Jude eventually finds himself embedded in a deep network of people who love and support him, his relationship with Willem is always his first reason to keep living. Willem is a marvelous character, both realistic and fantastical at once. He is compassionate and understanding in the extreme, and seems crafted by fate to walk with Jude through the flames that always threaten to engulf him. Willem is capable of appreciating his good fortune, and has hopes for Jude that Jude could never sustain without him:

What about life––and about Jude’s life, too––wasn’t a miracle?…Wasn’t friendship its own miracle, the finding of another person who made the entire lonely world seem somehow less lonely? Wasn’t this house, this beauty, this comfort, this life a miracle? And so who could blame him for hoping for one more, for hoping that despite knowing better, that despite biology, and time, and history, that they would be the exception, that what happened to other people with Jude’s sort of injury wouldn’t happen to him, that even with all that Jude had overcome, he might overcome just one more thing? (573)

Later, Willem explains what gives his life meaning:

“I know my life’s meaningful because”––and here he stopped, and looked shy, and was silent for a moment before he continued–– “because I’m a good friend. I love my friends, and I care about them, and I think I make them happy.” (687-8)

In a book crammed with murky psychological labyrinths, Willem’s refreshing outlook makes him the ideal companion for Jude. Willem is far from perfect, however, and struggles to find balance between his acting career and a relationship with Jude that is precarious and protean. With much effort, Willem eventually helps Jude learn to talk about his past, only to discover that verbal expression, despite some salutary effects, is not a restorative panacea. One of A Little Life’s most brutal lessons is that some wounds simply can’t be healed.

Perhaps the most courageous aspect of A Little Life is its determination to wrestle with relentlessly difficult moral problems in a completely nonreligious way. Although religion plays something of a role in Jude’s early life, it is entirely absent from his adult relationships and self-abusive habits. Never once do any of his friends or loved ones ask him about his relationship with God, or suggest religion as a path to redemption. This situates Yanagihara’s book firmly in the enlightened 21st century, where problems and their solutions are inherently contingent and local, and loving relationships form a flesh and blood shield against misery and loss. The non-presence of any immutable or metaphysical refuge makes Jude’s story that much more honest and profound.

Though it contains moments of elation and tenderness, A Little Life is a deeply tragic tale that pulls no punches and throws many. Hanya Yanagihara has tapped the hidden wellspring of human joy and suffering, and replenished it with a work of extraordinary value. Like all great novels, this one is an exercise in empathy, an examination of how and why people come to tolerate, understand and love one another:

He had looked at Jude, then, and had felt that same sensation he sometimes did when he thought, really thought of Jude and what his life had been: a sadness, he might have called it, but it wasn’t a pitying sadness; it was a larger sadness, one that seemed to encompass all the poor striving people, the billions he didn’t know, all living their lives, a sadness that mingled with a wonder and awe at how hard humans everywhere tried to live, even when their days were so very difficult, even when their circumstances were so wretched. Life is so sad, he would think in those moments. It’s so sad, and yet we all do it. We all cling to it; we all search for something to give us solace. (621)

For all its horrors, this book gave me lots of reasons to keep clinging to my own little life. Each of us can be to our loved ones what Willem and Jude are to each other––priceless and irreplaceable arrangements of matter that reveal the world as something wondrous and worthy of compassion.

I try to be kind to everything I see, and in everything I see, I see him. (720)

Rating: 10/10

Well done! Looks like something I would like to read!

Thanks for reading! The book is amazing. I hope you enjoy it.