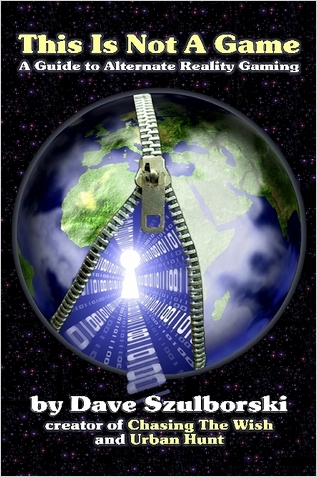

Book Review: Dave Szulborski’s “This Is Not a Game”

by Miles Raymer

I’d never heard of Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) until a friend suggested I read this book. As someone interested in the intersection between gaming and narrative, I think the ARG world is full of promise. Dave Szulborski has written a fine introduction to this embryonic genre; his tripartite offering is a conceptual manifesto, brief history, and instruction manual wrapped into one book.

The idea that ARGs are “not games,” which Szulborski refers to as the “TINAG philosophy,” denotes the special balance between fantasy and reality that makes ARGs unique. Played out in labyrinthine connections between websites, telephone numbers, addresses, physical locations, and other mediums, ARGs create an illusion of reality to draw players into the story. ARGs also have flexible storylines that can be influenced by player behavior to varying extents, similar to divergent plot structures in video games that respond to player choice. It’s a genre with seemingly limitless potential, but also a lot of room for technical snafus, which seem to have plagued many early ARGs to the point of rendering them far less immersive than intended.

Szulborski provides an in-depth explanation and analysis of the most notable ARGs that took place prior to his book’s publication. He seems to work well with what he’s got, which isn’t much. ARGs were (and probably still are) in their infancy in 2005, so there isn’t a very wide range of examples for Szulborski to critique. He also spends a lot of time talking about his own games, which is understandable but also a bit tiresome. Szulborski makes an effort to point out the flaws and missteps in his games, but can’t avoid coming off as self-promoting. It’s not deplorable in light of his important role in the ARG community, but obviates any pretense to critical objectivity.

This Is Not A Game is especially strong in its explanations of the technical challenges and necessities for pulling off a successful ARG. Szulborski has acted as Puppetmaster for a few different games and demonstrates a good understanding of his craft. The book’s theoretical framework, however, is less solid. Szulborski’s musings on the murky question of how we should define a “game” are complex but ultimately disappointing. Given the concept’s protean nature, it seems adequate to say that a “game” is pretty much anything a group of willing participants decide to call a game. More precise definitions invariably break down when held up to the vast range of activities designated as “games” around the world and throughout history. I suspect any search for a hard and fast definition will become even more futile as the barrier between storytelling and gaming becomes more permeable. Practically, it doesn’t matter whether ARGs are “games” or not––just that people enjoy them and want to participate in their creation/unfolding.

Szulborski seems to assume that ARGs will continue to grow in scale, frequency, and player interest. I agree that such trends are likely, especially as innovative models for new ARGs become tried and true. It’s also possible that ARGs could just be a fad, or (more likely) a type of game whose appeal will remain limited to a small niche of die-hard gamers who enjoy tracking down abstruse details and cracking codes.

With the lion’s share of ARG history almost certainly ahead of us, this book’s uses will be limited. However, there’s no question that Szulborski and his fellow Puppetmasters are pioneers of a sort, and anyone whose life has been touched––even just theoretically––by the ARG world owes them a certain gratitude. Though not particularly well written or intellectually compelling, This Is Not a Game effectively puts a new kid on the virtual block.

Rating: 5/10

Goodness! Fantastic Post. I truly tracked down this such a lot of informatics. It is the thing I was looking for I might want to propose you that kindly continue to share Such sort of data. Thank you kindly.

Happy to oblige and thanks for reading! 🙂