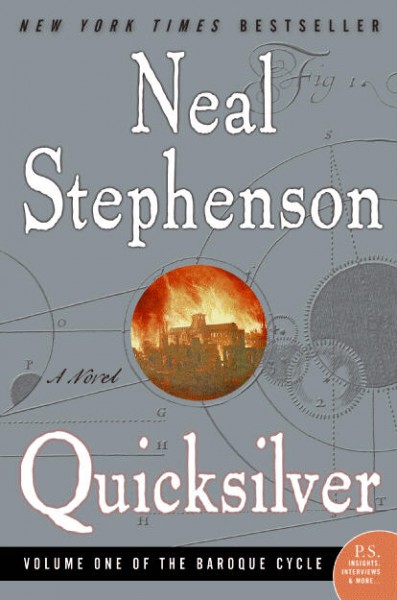

Book Review: Neal Stephenson’s “Quicksilver”

by Miles Raymer

It is always painful to write a negative review of a beloved author, but less so when the book in question is as desultory and tedious as this one. Neal Stephenson is probably my favorite living author, but making it through the first volume of his Baroque Cycle (which is really three books in one) was like taking a cross-continental flight through a turbid storm with only momentary glimpses of clear sky. Any experienced Stephenson reader expects to be bowled over by recondite descriptions of, well, pretty much everything, but Quicksilver displays the needless sprawl and lack of restraint that can render impotent even the most beguiling intellect. For a book that spans a considerable length of time during which things are constantly happening, there is a remarkable paucity of events, in the sense of emotional climax or meaningful developments in the story. The book’s bloated nature tarnishes Stephenson’s brilliance, exacerbating his worst tendencies and drawing back from his best.

Quicksilver takes place in late 17th century Europe, with small bits set in early 18th century not-yet-America. It is a fictionalized account of the intellectual, social, and political journeys of some of Europe’s most beloved thinkers, most notably Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz. This part of the tale is seen through the eyes of Daniel Waterhouse (ancestor of Lawrence and Randy Waterhouse from Cryptonomicon), a lesser savant who rooms with Newton in college and goes on to be a member of London’s Royal Society. There are two other main characters: Jack Shaftoe (ancestor of Bobby) and Eliza. Jack is a lovably audacious London-born vagabond who gallivants around Europe with an air of self-determination uncommon for the time period. On one of his many adventures, he meets Eliza and frees her from a harem during a battle with the Turks outside Vienna. They travel together for a time, eventually part ways, and Eliza becomes involved in Europe’s nascent currency speculation business.

These three characters, and a massive host of supporting ones, dance around each other throughout the novel, occasionally crossing paths or engaging in indirect shenanigans with mutual acquaintances. They experience many genuinely interesting things, but the book’s plot never quite decides which story it wants to tell, leaving the reader feeling as if Stephenson himself didn’t really know (or––more likely––that he simply didn’t care about adhering to plot conventions). This feeling of disconnection inhabits Stephenson novels with varying strength, but dominated Quicksilver in a way that was both distracting and disappointing.

Despite its many flaws, there is much to like in this 900+ page door-stopper. Daniel, Jack and Eliza all come to represent the tension between individualism and allegiance to monarchy that sprang from the Protestant Reformation and culminated in the American Revolution and the advent of constitutional democracies in Europe. Jack is especially flippant about authority and his own status as a person without status. Daniel, the Puritan son of a radical father, is a man whose considerable intelligence makes him useful to British aristocrats, but who is treated as an outcast due to his family history.

Describing Eliza is more difficult; she is definitely the character about whom I feel most conflicted. Equal parts proto-feminist and hyper-sexualized temptress, Eliza is a baffling contrast of progressive and anachronistic qualities. I don’t know if that’s what Stephenson was going for, but I was left with the nagging feeling that he wanted to write a character who was supposed to be a strong female in a male-dominated world. In this, he was partially successful. Eliza’s strong qualities are diminished somewhat by Stephenson’s tendency to overemphasize her body as a sexual object of the male gaze. Even worse, Eliza is sometimes blasé about her own sexuality in a way that just didn’t sit right with me. In one particularly disturbing scene, Eliza is coerced into performing fellatio on a nobleman. This is her thought just before capitulation: “What was about to happen wasn’t so very bad, in and of itself” (599). Now, it’s perfectly possible (although I suspect not probable) that someone in this situation could have such a thought, and also that a woman sold into a 17th century harem might be casual about being forced sexually, but in this case Stephenson’s writing really bothered me. Eliza is assertive with her intelligence and sexuality at other points in the story, and is certainly not a simplified caricature. But too often she comes off as a kind of pornographic fantasy that just happens to have a brain and some guts.

In general, this novel does a great job of reminding the reader that most humans lived before modern scientific thinking and the plethora of technologies it spawned. Quicksilver is situated at a tipping point in Europe’s historical conversation about what the world is and how we should live in it. Daniel and Jack both represent the struggle between predestination and free will that was taunting Europe’s elite. The idea of scientific truth “pushing back the veil of God” is front and center in the novel’s best moments, with some of history’s biggest minds obsessing over the paradox of how to justify the existence of (or need for) omniscient will within an increasingly understandable set of natural laws. Stephenson’s prose wields its characteristic cleverness and erudition, but his attempts to utilize certain Baroque writing elements largely fall flat, adding little to the reader’s engagement in the story and providing ample opportunity for inanition.

My problems with this book stem from the fact that I’m not a European history buff. If I were, I’m sure many of the passages I found absolutely boring would have had me begging for more. The tidbits of intellectual history were fascinating, and I occasionally enjoyed learning about an old type of building, tool, or cultural practice, but more often than not Stephenson’s tangents proved mere distractions from the main story (what little of it there was). The worst part was the politics. I usually eschew the historical details of monarchies, which, as unique and raunchy as they can sometimes be, always amount to the same old shit: assholes trying to get the upper hand on other assholes. I can occasionally get sucked into power-centered narratives like Game of Thrones or Shogun, but such stories need to be emotionally visceral to keep my attention. I really don’t care how Louis XIV and his sycophantic horde of admirers spend their days at Versailles while working people suffer. I don’t care who the next King of England will be, because I’m too modern-minded to want any king at all. Stephenson seems to expect readers to find monarchical plots and authority struggles interesting in and of themselves, and does little to enliven protracted lists of people and events that ultimately have little influence on Quicksilver’s story or characters.

I also don’t care much about the history of money, which plays a large role in this book; it’s just a topic that draws Stephenson’s interest but repels my own. In his other works––most notably Reamde––Stephenson has evinced in me a fascination with objects and methods about which I have little knowledge and less interest, but Quicksilver couldn’t grab my attention enough to challenge those boundaries.

My biggest regret here is that I became so annoyed with this book that I stopped reading very closely after the first few hundred pages. I just didn’t get enough bang for my buck by paying close attention, so once I learned who the important characters were, I began hunting for them and skimming paragraphs that clearly weren’t going to teach me anything I wanted to know. It’s also true that elements of this book were simply over my head. And while I managed to follow the story just fine, I’m sure there were plenty of fun and even profound moments along the way that I missed. But I also made short work of a lot of dense gobbledygook.

In its finest moments, this book is fantastic––as good as anything one could hope to read. But therein lies the problem: because Stephenson sets such a high bar, it’s hard to take it when the overall effect doesn’t prove earth-shattering. My quarrel with Quicksilver is no doubt due in part to my own intellectual shortcomings and parochial interests, but I also think the book contains some objectively obnoxious and dull qualities. Even so, I love Stephenson and will press on with the Baroque Cycle because I am invested in reading his corpus. He can be a real pain in the ass, but he’s worth it.

Rating: 5/10

[…] into the wordy quagmire that is Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle. As with Quicksilver, this volume contains a considerable dose of magical moments dissolved in a nearly impenetrable sea […]

[…] man, Daniel returns to London to complete the task assigned to him way back in the first scenes of Quicksilver––the reconciliation of long-estranged geniuses Sir Isaac Newton and Wilhelm Gottfried […]