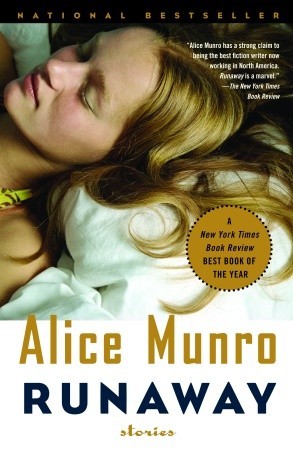

Review: Alice Munro’s “Runaway”

by Miles Raymer

“The mind’s a weird piece of business,” Alice Munro observes toward the end of this magnificent collection of stories (308). Munro is certainly right about that; her perspicacious and adroit writing shows that she understands human quirks and foibles better than most writers, even the exceptional ones. My initial reaction to many of the stories in Runaway was something like: how it is possible that I haven’t read anything by Alice Munro until now? Munro has certainly garnered the recognition she well deserves (most recently by receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature), but after my first personal encounter with her work, I’m still left wondering why she isn’t a household name across the entire English-speaking world.

Munro reminds us that the short story should never be left out of the running when trying to delineate humanity’s highest forms of artistic expression. She seems to have made a kind of devil’s pact with the deities of the short story miniverse, the opaque terms of which have bestowed on her near-godlike linguistic powers. Though it would be foolish to waste too many words trying to capture how it feels to read one of Munro’s stories, there are a few key elements of her talent that deserve special mention.

Something that becomes clear just a few pages into this book is that everything in Munro’s writing––every descriptive paragraph, offhand comment, and quiet rumination––is significant. The meanings embedded in each story are highly plastic and open to interpretation, keeping them from becoming trite or heavy-handed; everything means something, but it’s not always easy to tell exactly what. Yet the stories aren’t so amorphous that they deny an objective reality shared by overlapping but distinct subjectivities. This is exactly what real life is like, at least for meaning-making creatures like us. We are constantly imbuing our environment with messages, connections, and symbols, and trying to match them up with the inner lives of others, insofar as we can model them via observation, communication, and thoughtful revision. Munro reflects this process back on itself, creating fictional mediations between our raw sensory experiences and our far-flung, imaginative inner lives. Simply put, she does what any truly superior writer does, and she does it as well as anyone.

Munro exposes the mystery of our mundane existences, showing how it is often the unanticipated moments or situations that have disturbingly large influence on the course of lives. She toys with causality and fate without endorsing (or explicitly denying) determinism, seeding a rich, inquisitive interpretation of the world as the unfinished site of testable hypotheses. This broad filter transforms seemingly dull situations into strokes of insight. Her elegant and transparent prose generates a plethora of possible images so unobstructed that one often forgets they are being transmuted through the written word.

One character in Runaway’s eponymous story envisions the possible consequences of her flight from an oppressive home:

The strange and terrible thing coming clear to her about that world of the future, as she now pictured it, was that she would not exist there. She would only walk around, and open her mouth and speak, and do this and do that. She would not really be there. And what was strange about it was that she was doing all this, she was riding on this bus in the hope of recovering herself. As Mrs. Jamieson might say––and as she herself might with satisfaction have said––taking charge of her own life. With nobody glowering over her, nobody’s mood infecting her with misery.

But what would she care about? How would she know that she was alive? (34, emphasis hers)

Another character in a different story discovers the truth about a potentially life-changing romantic misunderstanding that occurred decades ago:

It was all spoiled in one day, in a couple of minutes, not by fits and starts, struggles, hopes and losses, in the long-drawn-out way that such things are more often spoiled. And if that’s true that things are usually spoiled, isn’t the quick way the easier way to bear?

But you don’t really take that view, not for yourself. Robin doesn’t. Even now she can yearn for her chance. She is not going a spare a moment’s gratitude for the trick that has been played. But she’ll come round to being grateful for the discovery of it. That, at least––the discovery which leaves everything whole, right up to the moment of frivolous intervention. Leaves you outraged, but warmed from a distance, clear of shame.

That was another world they had been in, surely. As much as any world concocted on the stage. Their flimsy arrangement, their ceremony of kisses, the foolhardy faith enveloping them that everything would sail ahead as planned. Move an inch this way or that, in such a case, and you’re lost. (268-9)

These passages are poignant examples of Munro’s deep relationship with the contingencies and challenges faced by self-reflective beings. We live only one life, and yet possess the ability to bathe in all our imagined possibilities at virtually any waking moment. This can be our salvation or our unremitting hell, and it is usually both. These are the facts of life, ones with which all adults are more or less familiar. But somehow Munro funnels new light into them, teasing our longing for novelty while simultaneously returning us to our most essential selves.

In one of a sequence of three excellent stories that revolve around the same protagonist, Munro claims that, “Few people, very few, have a treasure, and if you do you must hang on to it. You must not let yourself be waylaid, and have it taken from you.” (84). Thanks to Munro’s ability to articulate her huge heart and stunning mind, the whole world can discover a new treasure. I will make it a goal to read her corpus––a journey that, once completed, no one will ever be able to take from me.

Rating: 10/10

This has to be one your most praising reviews ever written. I look forward to picking this book up and wish now that I would have grabbed her other two at the library book sale.

Well, let’s see if you like her before you buy all her books! I’m not sure Alice Munro is everyone’s style, but I definitely think she is superb.