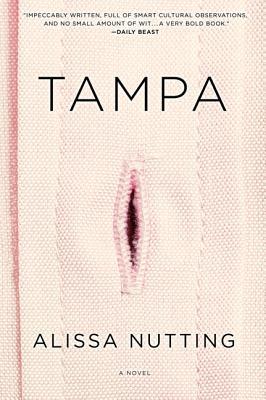

Review: Alissa Nutting’s “Tampa”

by Miles Raymer

This fiendish novel dug its claws into me and didn’t let go until the very last page. Alissa Nutting’s Tampa is rich in imagery and metaphor, teeming with keen observations about the dark sides of American culture, and saturated in seduction. It’s a book that would have overflowed with its own verve if Nutting hadn’t been smart enough to keep it short and sharp. Plunging headfirst into our cultural obsessions with youth and beauty, Nutting weaves a good story while also exposing a handful of deeply troubling suggestions about how we get stuck in ourselves and how malice spreads from one human body to another.

To read Tampa is to enter the remarkably fucked-up head of Celeste Price and not be allowed to leave. Celeste is a drop-dead gorgeous sociopath with an unstoppable penchant for sexual predation. Her targets: 14-year-old boys. The book opens with her excitement over the impending payoff from years of hard work to get exactly where she wants to be. As the new Language Arts teacher at a junior high school in Tampa, Florida, she will have ample opportunities to expel from her body the violent and persistent sexual urges that dominate her internal monologue. Though this premise may seem flimsy and lewd, Tampa is much more than a smutty tale of taboo sexual transgression. It is that, of course, but it is also a careful and compassionate examination of human aberration. For all of her wickedness, I gained a remarkable amount of sympathy and respect for Celeste over the course of the novel. It is a testament to Nutting’s talent that she was able to write a character who is deplorable, pathetic, and hyper-competent all at once. Celeste is the kind of person we’d all hate to encounter in real life but relish from a safe fictional distance.

Another important aspect of her appeal is that, unlike a hypothetical male protagonist with similar proclivities, Celeste pursues willing prey. It’s hard to imagine that many 14-year-old girls would submit to the entreaties even of a very attractive and youthful male teacher, but your average 14 year-old-boy, awash in hormones and inexperience, would likely jump at the chance of a secret rendezvous with a hot female authority figure. Celeste does have to choose her marks carefully to ensure discretion, but could probably have her pick of the litter in a less volatile situation. One of my favorite parts of the novel was the reawakening of uncomfortable remembrances about my own life as an 8th grade boy. If I’m honest, I don’t think there’s much chance I could have resisted a creature like Celeste, even if I knew going along with her was a bad idea. The disturbing fact is that pubescent boys crave this sort of adventure––or at least they think they do.

Nutting understands well the essential tension between adolescent lust and youthful innocence, and it is Celeste’s perverse obsession with this mixture that drives her. Remarking on the satisfactory nature of her first triumph, she crows: “I’d be the sexual yardstick for his whole life: Jack would spend the rest of his days trying but failing to relive the experience of being given everything at a time when he knew nothing” (96). Her celebration of what is an essentially disastrous situation for Jack reveals Celeste’s deep divorce from the feelings of others. Despite her lack of empathy, she wields an impressive ability to simulate others’ motivations and possible actions in her mind’s eye. It is her ability to do this without attaching emotional content to the imaginative act––a classic sociopathic trait––that makes her effective in her pursuits and sinfully fun for the reader to follow.

Celeste’s flawless physique and preoccupation with young boys also render her a disturbing symbol for how American culture regards the idea of youthfulness. It’s as if Celeste, for whatever inherent or environmental reason, became mentally frozen in time even as her body kept aging. This is the exact opposite of what many people wish for themselves––for the mind to grow wiser and more experienced while the flesh is sequestered from time’s onslaught. Thinking back on youth, it is so easy to forget the insecurities, the powerlessness, and the tumultuous fervor of rapid growth. Celeste’s sickness reminds us that even though we may sometimes feel this way, the notion that “The adult world has so much less to offer than adolescence does” is one of our most pernicious lies (140).

Like any tale where characters take massive risks to get what they want, this one comes to a tense climax, the results of which are probably less disastrous for Celeste than she deserves. She proves slippery and resourceful to the end. More important than her final destination is her lasting effect on the boy Jack, who enters manhood with a newfound sense of isolation and distrust. In a gut-wrenching scene, Celeste recognizes (dispassionately, of course) the change in Jack as something transferred directly from her into the boy’s young heart:

Jack stayed for a moment, crying, then looked over at me. It wasn’t at all the look of hatred I’d expected. Instead it was a look of mutual knowledge, Jack conveying to me his new understanding that the world could be a terrible place. His eyes said that no one at all was looking out for him or able to fix this essential flaw in life’s fabric; my eyes stared back and told him that he was right. (259-60)

The tragedy of Celeste’s own unacceptable nature has migrated, re-spawned, taken on new life inside a fresh host. Dressing itself as the answer to a prayer, evil finds a way.

Rating: 8/10

Wow! You should have written the dust cover Miles. Now I really want to read this one.

Thanks! I look forward to hearing your thoughts after you read it.