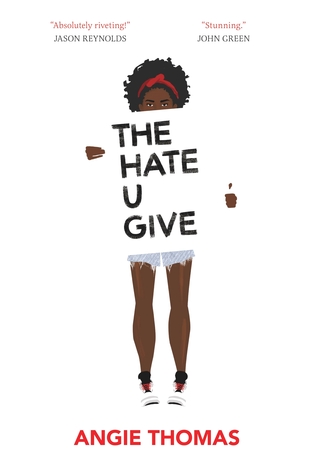

Review: Angie Thomas’s “The Hate U Give”

by Miles Raymer

Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give was recommended by a friend who thought reading it would be a good experience for me, and she was right. I struggled with this novel for a few different reasons, but ultimately found that it was worth the effort. It is always useful to engage with new perspectives, and I think I’m now able to better express my opinions regarding how I think and talk about racial tensions and police violence in contemporary America.

Before proceeding any further, I’d like to acknowledge something: The Hate U Give describes situations and viewpoints that, although authentically American, feel extremely foreign to me. I don’t consider myself capable of assessing whether the speech and/or behavior of the characters is realistic, nor do I personally understand how being a minority in America or a victim of police violence affects one’s internal experiences. This review is written with those contextual truths in mind.

The Hate U Give is a story about Starr, a 16-year-old African-American girl. Starr seems a typical teenager in most ways, but it’s hard to tell because the reader is only given one chapter to get to know her before she witnesses a police shooting that leaves her traumatized and turns her life upside down. The victim is Khalil, one of Starr’s childhood friends; he is gunned down by a police officer during a traffic stop while Starr looks on in horror from the passenger seat. Although Khalil is slightly rude to the officer, there’s nothing in his comportment that clearly identifies him as a threat, and certainly nothing that justifies the use of deadly force.

In the aftermath of this awful event, we meet Starr’s family and community. She lives in Garden Heights, a struggling neighborhood that is dominated by local gangs. Her family is a hard-working, tight-knit bunch who get by without direct involvement in the drug trade. In an effort to give Starr and her siblings a good education in a safer locale, her parents have enrolled them in Williamson Prep, a school outside their neighborhood with a predominantly white and upper-class student body.

Starr does a lot of code-switching––linguistic as well as cultural––in order to adapt to whatever environment she happens to be in. She explains:

I just have to be normal Starr at normal Williamson and have a normal day. That means flipping the switch in my brain so I’m Williamson Starr. Williamson Starr doesn’t use slang––if a rapper would say it, she doesn’t say it, even if her white friends do. Slang makes them cool. Slang makes her “hood.” Williamson Starr holds her tongue when people piss her off so nobody will think she’s the “angry black girl.” Williamson Starr is approachable. No stank-eyes, side-eyes, none of that. Williamson Starr is nonconfrontational. Basically, Williamson Starr doesn’t give anyone a reason to call her ghetto. I can’t stand myself for doing it, but I do it anyway. (71)

For me, this was the most interesting aspect of Starr’s character. From the first page, it’s clear that her self-image is split between two identities, and watching her navigate them is entertaining and enlightening, especially for someone who hasn’t had to do nearly as much code-switching in his life as someone in Starr’s situation.

Starr’s two selves complicate her interactions with her boyfriend, Chris, who is white and wealthy. As their relationship develops, we get to witness two young people from very different backgrounds learn to understand themselves and communicate in new ways––to respect differences while celebrating commonalities. Starr has many other peer relationships that she maintains in both worlds; these take up the majority of the book’s page-count and vary in quality from genuinely intriguing to just boring. Despite a serviceable ability to craft decent characters and plug them into a topical sequence of events, Thomas’s writing does not exhibit much ingenuity at this early stage in her career.

I wasn’t able to connect very well with Starr as a narrator and found her peers to be similarly bland, but the adults in her life proved much more engaging. Her parents, Maverick and Lisa, are both well-drawn characters who’ve made a good life out of difficult circumstances. I didn’t always agree with their opinions, but they earned my interest and respect as I learned more about them.

The main conflict between Maverick and Lisa is the question of whether they should move out of their crumbling community and into a neighborhood that will be safer for their kids and provide more educational and economic opportunities. It’s a tough dilemma with legitimate arguments on both sides, as demonstrated by this exchange:

“A’ight, let’s say we move,” Daddy said. “Then what? We just like all the other sellouts who leave and turn their backs on the neighborhood. We can change stuff around here, but instead we run? That’s what you wanna teach our kids?”

“I want my kids to enjoy life! I get it, Maverick, you wanna help your people out. I do too. That’s why I bust my butt every day at the clinic. But moving out of the neighborhood won’t mean you’re not real and it won’t mean you can’t help this community. You need to figure out what’s more important, your family or Garden Heights.” (180)

Although Thomas does a good job of portraying the specificity of the choice confronted by Starr’s family, the general predicament is one to which many readers will easily relate: When an institution and/or community begins to break down, should we fix it from the inside out or from the outside in? There is, of course, no single right answer to this question; it depends on the individual(s) involved and the context. Starr’s folks butt heads about this issue a few different times, and eventually come to a resolution that I found both believable and satisfying.

The other character who won my allegiance was Uncle Carlos, Lisa’s older brother. He’s a member of the local police force and a colleague of “One-Fifteen”––the officer who murdered Khalil. The case gets messy when investigators learn that Khalil was a sometimes-drug dealer, which plays badly in the media even though Khalil had no drugs or weapons in his possession when he was killed, and the traffic stop was not drug-related.

Thomas doesn’t deign to explore the internal perspective of One-Fifteen, a choice about which I remain ambivalent. She does, however, effectively utilize Uncle Carlos’s point of view as a window into how groupthink can cause police departments to defend the indefensible. At first it seems that Carlos accepts the idea that Khalil may not have been an innocent victim, but as the facts of the case are better understood (and twisted in One-Fifteen’s favor), he becomes a noble agent of dissent:

“I knew that boy. Watched him grow up with you. He was more than any bad decision he made,” he says. “I hate that I let myself fall into that mind-set of trying to rationalize his death. And at the end of the day, you don’t kill someone for opening a car door. If you do, you shouldn’t be a cop.” (256)

I tried to grant The Hate U Give as much benefit of the doubt as I could reasonably muster, but in the final analysis there was one hurdle I couldn’t clear: Thomas’s repeated use of race-essentialist language. The book is peppered with obnoxious statements about the supposed preferences and character traits of “white people.” Here are some samples:

“I bet they be doing Molly and shit, don’t they?” Chance asks me. “White kids love popping pills.”

“And listening to Taylor Swift,” Bianca adds. (9-10)

On a serious tip––white people are crazy for their dogs. (116)

“Dude wearing J’s. White boys wear Converse and Vans, not no J’s unless they trying to be black.” (235)

According to DeVante, Chris’s massive video game collection makes up for his whiteness. (284)

White people assume all black people are experts on trends and shit. (294)

“Wait, wait,” Seven says over our laughter, “we gotta test him to see if he really is black. Chris, you eat green bean casserole?”

“Hell no. That shit’s disgusting.”

The rest of us lose it, saying, “He’s black! He’s black!” (398)

Now, as already stated, I’ve got no idea if these are realistic examples of how today’s teenagers actually think and talk about race. Additionally, it should also be obvious that these are not particularly inflammatory statements, and definitely don’t deserve to be labeled as racist. But here’s my problem: if in fact these are realistic examples of contemporary teen banter, then that is a sorry state of affairs.

It’s sad to think of America’s youth conversing in such silly, oversimplified terms about members of any race. Such expressions are neither socially useful nor descriptively accurate, since it is meaningless to say that any group of people who merely share the same skin color are “like” anything at all. To be fully comfortable with the statements targeted specifically at white people (which is most of them), readers have to be willing to perform the wacky intellectual backflip––all too common these days on the far left––of believing that race-essential language is fine as long as it’s directed at white people (the oppressor) and not people of color (the oppressed). Anyone who wants to retain their intellectual integrity by refraining from such thinking is going to be annoyed (but probably not outright offended).

Assuming that Thomas and her editors decided to include this kind of language in order to faithfully portray how kids from these backgrounds behave, I think they gave up more than they gained. I guess some readers might find these sections funny, but the unfortunate likelihood is that they will be cherry-picked by conservatives and alt-righters seeking to denigrate or ignore Thomas and others like her. This wouldn’t matter if the race-essentialist parts added something worthy to Thomas’s message, but as far as I can tell that’s not the case. Mostly it seems like she’s using them for cheap laughs, and not to tell the reader anything useful or interesting about this world or the people in it.

One could argue that The Hate U Give is just a novel and shouldn’t be politicized in this way, but that would contradict the entire subject matter and tone of the book itself, which is quite obviously trying to project an important and worthwhile set of socio-political lessons that all Americans ought to consider. When that’s your goal, it’s not smart to give your opponents easy ways to misrepresent your point of view and tear you down. Additionally, you run a greater-than-necessary risk of alienating readers like me who agree with your message but despise race-essentialism and don’t want to consume or promote books that contain even light-hearted, goofy versions of it.

All of that said, reading The Hate U Give was a valuable way to spend my time. I’m with Starr when she says, “Now we have to somehow un-fuck everybody” and “I’m not giving up on a better ending” (432, 443). These are the empowering and unifying proclamations that will lead to a world where future generations read this book and wonder how we ever could have been so foolishly obsessed with race and so shamefully comfortable with police brutality.

Rating: 6/10