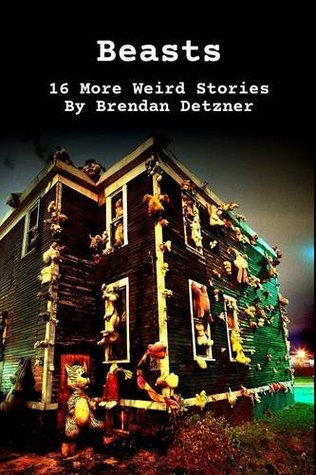

Review: Brendan Detzner’s “Beasts”

by Miles Raymer

This is definitely not a book I would have come across had Mr. Detzner not offered me an advanced reading copy in exchange for an honest review. It’s fun to get an early look at a new piece of fiction, but this short story collection struggled to capture my attention. I spent more time thinking about how the stories could be improved than I did enjoying them.

Right from the beginning, Detzner’s choppy writing made the stories tough to get into. The ARC text doesn’t seem to have gone through a proper editing process, and contains a handful outright errors as well as many sentences in need of serious revision. Take this example from the first paragraph of the first story:

As Shawna got older and gained a better understanding of her circumstances, the rule made less and less sense––her family lived in a trailer park and privacy was mostly a foreign concept, everybody knew exactly what was going on––but still, she never did tell anyone, even after her mother died. (loc. 51)

There are at least two separate sentences here, maybe three. It’s possible he could have scraped by with a well-placed semicolon, but he didn’t even try that. As it is, this sentence has almost no flow to it, and I had to read it a few times before I could even begin to consider its content.

Here’s another example from a different story: “More then once, if he had to, but he was a big guy, he didn’t think he’d have to do it more then once” (loc. 939). This short sentence manages to confuse “then” and “than” twice, and also contains a comma splice.

Now, in one sense it’s pedantic to harp on these relatively minor errors; they certainly aren’t egregious enough to discredit Detzner’s book altogether. But they also aren’t entirely negligible. Flow matters. Editing matters. Detzner’s words too often get in the way of his stories, rather than facilitating them. I’d be lying if I said this problem isn’t holding Beasts back.

Also confounding is Detzner’s abortive style. Most of his stories are remarkably short, which isn’t a problem in itself. But more often than not they fail to elicit much of an emotional or intellectual response. This is due to a general lack of character development and a dearth of description, especially in the expositions. Detzner’s voice has an oneiric feel, with more than a touch of the macabre, and clarity doesn’t seem to be a priority. (It’s also possible I missed some of the subtler signposts that would have helped me understand the stories better, but on the whole I wasn’t motivated to expend too much energy looking for them, which is another problem altogether.)

When trying to write stories that bemuse or horrify, the author must give up enough information to draw the reader in, but never quite reveal his or her full hand. Too little opacity will kill the mystery, while too much will leave the reader more confused than anything else. The majority of Detzner’s stories lack this balance, and are so concerned with being vaguely menacing that there’s little opportunity to develop a genuine investment in the characters and their problems.

Happily, this trend is not without exceptions. Two stories stood out to me as real gems. The first is “Spirits of the Wind.” This story is considerably longer than the others, and much more complex. It tackles timely issues such as socioeconomic hardship and America’s racial divide, blending them with elements of fantasy and jazz music. “Spirits of the Wind” nicely displays Detzner’s bizarre sensibilities, and indicates how they could be put to better use if he spent more time and effort developing his ideas into longer, more fleshed-out narratives.

I also enjoyed “PCFB,” a brief tale about a superintelligent computer that decides the pinnacle of human experience is partying at Panama City Beach, Florida. AI is one of my favorite topics in both nonfiction and fiction, and I thought Detzner’s treatment, though flippant, was also funny and insightful. The problem of using quantitative measures to assess the quality of human experience won’t be going away anytime soon, and “PCFB” is a great way to keep the discussion going, especially for those new to the AI debate.

As a final thought, I’d like to highlight a moment when Detzner unwittingly reveals his own weakness as a writer. “Mysteries are cool,” he bluntly proclaims. “Facts are boring” (loc. 1870). What is missing from Beasts is an understanding that the relationship between mystery and fact is a symbiotic one. The power of mystery to titillate and tantalize is rooted in the facts of human life––mundane moments and details that make us feel at home. Once that dynamic is established, we can be persuaded to feel like the supernatural might be just around the corner. But Beasts is lopsided, asking us to accept the unknown without first putting in the effort to show us a world we can truly relate to.

Detzner’s work flees from the facts of life more than it embraces them, and therefore dons the cloak of mystery without really earning it. Going forward, this promising author should try to keep his feet a little more on the ground, while still striving to keep his head in the clouds.

Rating: 5/10