Review: Jim Robbins’s “A Symphony in the Brain”

by Miles Raymer

While exploring my new career goal of entering the mental health profession, I recently met a LCSW in my community who offers neurofeedback as a supplement to other therapeutic services. Eager to share her enthusiasm for this technique, she generously gifted me a copy of Jim Robbins’s A Symphony in the Brain. My honest first impression was that neurofeedback seemed like a weird “alternative” practice––the kind that usually turns out to be pseudoscience, probably enabled by an elaborate, technologically-enhanced placebo effect. And while the science doesn’t seem to be entirely settled when it comes to this question, Robbins’s book convinced me that my initial judgment was too hasty and too strong; neurofeedback, it turns out, has a long and intriguing history, a burgeoning bevy of contemporary practices, and a horizon of possible futures that merit attention and further research.

A Symphony in the Brain was originally published in 2000, and the revised edition (the version I read) was released in 2008. So while this book doesn’t contain the most up-to-date information about current practices and studies, it provides a solid look at the fundamental principles that gave birth to neurofeedback and fueled its development starting in the early 20th century.

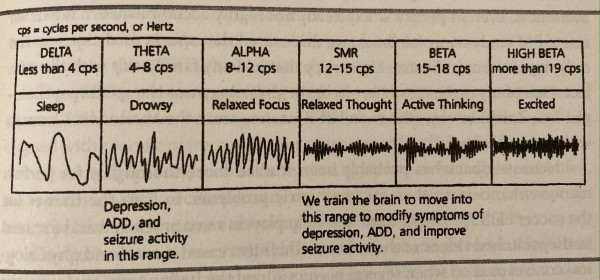

Neurofeedback is a type of biofeedback that uses electroencephalography (EEG) to translate a brain’s electrical signals into some form of output, usually visual or auditory. It involves attaching electrodes to a person’s skull, and then giving that person real-time access to the data the electrodes are pulling from their brainwaves. Parameters can then be set to provide a “reward” (pleasant stimulus) when brainwaves register within a desired bandwidth––typically alpha, sensorimotor rhythm (SMR), or beta, depending on the type of treatment and patient goals. Practitioners claim that, over time, this type of training can help a person achieve healthier, calmer, and more productive “default” brain states, and also become more resistant to distractions. Here’s a helpful image I pulled from Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score:

Robbins defines neurofeedback as “the operant conditioning of autonomic function,” and posits that it may allow people to consciously align our everyday brain states with our intentions and goals (xiii). He explains:

Most human beings––and this may be the most profound lesson from all neurofeedback––are simply not inherently or irrevocably flawed. Instead, many––perhaps most––of the problems that plague humankind are a case of “operator error.” We “own” our central nervous system to a far greater degree than we imagine. We can get our hands on the steering wheel and deal with anxiety, depression, ADD, and a wide range of other problems. Neurofeedback shows us how powerful we are. (xv)

The book’s central metaphor, as the title suggests, is that of a symphony, with a well-organized mind being able to occupy more harmonious, creative, and productive forms of consciousness that minimize suffering, increase focus, and light the path to greater happiness and flourishing. In this view, people suffering from psychological disorders struggle to properly “conduct” the orchestra inside their own head:

Neurofeedback, the model holds, rouses the conductor and resets him to his appropriate speed. Once the conductor is back in form, the rest of the players fall into line. Whether the problem is autism, epilepsy, post-traumatic stress disorder, or any of a host of other maladies, the answer lies in resetting the conductor and appropriately engaging the orchestra with neurofeedback. (31)

These are very encouraging sentiments proffered in pretty words, but what are the actual biological mechanisms that neurofeedback is harnessing? The short answer, as Robbins notes several times, is that we don’t exactly know. There are lots of theories, most of which comport with our general knowledge of neuroscience, but none of them is considered a “proven” theory. Here are a couple examples:

One hypothesis about what might be going on in the brain during neurofeedback has to do with the way the cells in the brain connect with one another. Since information travels along the branchlike connections between cells called dendrites, the denser and greater in number these connections are, the better the transfer of information. As frequency increases during a neurotherapy session and the brain is activated, more blood than usual streams to that area of the brain––the nutrients in the blood may be strengthening or reorganizing existing connections, which increases the cells’ ability to self regulate. This is what many scientists think happens during any learning process. (Brain scans show that in people who go blind and learn Braille, the neurons in the area that governs their reading finger become more robust.) The neurofeedback model holds that the brain wave training increases the stability of that area of the brain as well as its flexibility, or its ability to move between mental states (from sleep to consciousness or arousal to relaxation, for example). It allows the players in the orchestra to play their parts better, to find the correct tempo, to come in on time, and to stop playing when they aren’t needed. Since every aspect of a person is driven by an assembly of neurons, the healthier those neurons are, the healthier are the functions that they govern. (45)

When the brain is trained with neurofeedback, blood bathes the cells in the frontal cortex and acts as a kind of fertilizer helping cells overcome malformation, due either to genetics or perhaps from cortisol damage caused by emotional stress. Existing connections are strengthened or reorganized, or perhaps they grow new branches. Whatever the case, they make better, more robust connections with adjoining cells, and so the transfer of current and neurochemicals works much faster and more efficiently. (137)

Notice Robbins’s use of terms like “stability,” “flexibility,” “more robust,” and “more efficiently” as descriptors for neurofeedback’s positive effects. Depending on your familiarity with neuroscience, you may find this language convincing or annoyingly vague. I land somewhere in the middle; I don’t think these terms are entirely meaningless in this context, but they can also feel frustratingly imprecise. This is a general problem with how proponents of neurofeedback talk about and sell it. I think it’s one of the main reasons why neurofeedback has had trouble being accepted as an allopathic (science-based) treatment, both by the medical establishment and the general public.

Another weakness is that neurofeedback enthusiasts sometimes wander too far in the direction of oversimplification. At one point, Robbins describes the “Othmer model” of mental illness, which was invented by Sue and Siegfried Othmer, two of the earliest and strongest neurofeedback advocates. The Othmers assert that all mental illness diagnoses fall into just three categories: chronic overarousal, chronic underarousal, and “brain instability” (201). “The model is a move back to a much simpler time in neuroscience,” Robbins writes, “and to a much simpler time in psychology… The Othmers have essentially thrown out most of the hundreds of diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (201-2). I’m in no way convinced that the DSM is the only or even the best way to successfully understand and treat mental illness, but I also have strong doubts that the many decades and countless careers that have gone into compiling that resource can be easily dismissed in favor of the Othmers’ framework.

My last criticism concerns doubts about the wide variety of situations where neurofeedback can supposedly help people. This includes not only a profusion of mental health challenges, but also performance enhancement for athletes, musicians, and businesspeople, and even claims of inducing spiritual enlightenment at the field’s outer edges. At some points in the book, the scope feels “unbelievably broad,” as Robbins puts it (198).

To his credit, Robbins engages repeatedly with all of these problems, highlighting good reasons for skepticism and caution. I especially liked the sections focusing on Joel Lubar, a pioneer in using neurofeedback to treat Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). “Lubar is worried,” Robbins writes, “that the fringe reputation the field already has will get worse if clinicians move too far too fast and the claims once again get way out beyond the research” (198). This seems like the optimal position, and Robbins joins with many others by insisting that neurofeedback is “neither miracle nor panacea,” and that the “true scope of brain wave training” is yet to be determined (3, 244). He also points out––fairly, in my view––that there are similar concerns about many psychotropic medications that doctors and psychiatrists routinely prescribe as part of the “medical model” of mental illness.

In the end, many key questions remain unanswered:

After years of research on neurofeedback, including my own experience and the experience of family members, I am no longer skeptical about whether it works. Instead, The questions are about the scope of the success: what percentage of people respond dramatically and successfully? Miracle stories are fascinating, but how often do they happen? How many people get something out of it but not a transformation? How many don’t respond at all? How long does it last? Can neurofeedback cause problems? If the efficacy question has been, with few exceptions, poorly researched, these kinds of questions have barely been touched. (217)

I’m not sure about the extent to which these questions have been explored or answered in the years since this book came out. But Robbins left me eager to learn more through his honest portrait of the diversity of opinions within the neurofeedback community, driving home its underdeveloped character while also trying to preserve its promise:

One of the most exciting things of all is that the field is in its infancy. Clinicians and researchers have been laboring away in their own little corners, with few resources and a great deal of imagination and determination, believing what they have found is the best, and rarely venturing out to talk with others in the field. The story of neurofeedback may, at present, be akin to the story of the blind men and the elephant, in which each man thinks he knows what the elephant looks like from feeling one part of it. Each in reality has only a partial claim on the truth. Each of the neurofeedback pioneers has taught the brain, in his or her own way, to play a piece of music. But no one has brought all of the instruments and players and music together. That grand and complicated and beautiful piece of music has yet to be played. (246)

This book wasn’t as impactful or informative as some of the other therapy-related books I’ve read recently, but it provided a welcome challenge to my initial assumptions and personal biases. The quest for long-term growth requires approaching new topics with an open mind, and Robbins helped me do so without feeling like my mind was so open that my brain fell out.

Rating: 6/10

This brings to mind a technique I picked up from an episode of Radiolab. Stick an anxious person in an MRI and show them a visual representation of their brain activation associated with the anxiety. In the example they use a fire. As people get the visual feedback from their brain they are able to calm it and watch the fire get smaller.

In need of more tools for my mental health tool bag I thought let me give that a try. Can’t hurt. I found it times of anxiousness or similar disruptive feelings it worked well for me to just close my eyes and visualize the feeling as a bonfire. I would then in my mind watch it shrink until it was just a normal fire or burned embers. For me this was and still is super effective. The main difference is I just feel a lot less anxious on the whole so I rarely need to use it now but it was a big help.

Wow, what a great story! This seems like a low-tech form of biofeedback/neurofeedback that utilizes the mind’s native internal imagery as opposed to hooking you up to electrodes and a computer. Thanks for sharing and glad that you have this mental health tool at your disposal! 🙂

Amazing , this article is informative and is very beneficial to all the readers. I appreciate this, because I learned many things about the topic.

Thanks Pans for reading and leaving this nice comment. I appreciate it! 🙂

I appreciate this article, this is indeed great. Simply because the content is very useful and informative especially to the ladies. Thank you for sharing thiIs.