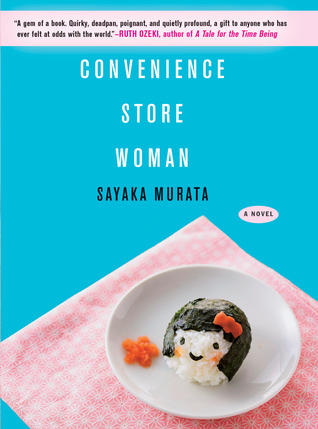

Review: Sayaka Murata’s “Convenience Store Woman”

by Miles Raymer

Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is a diminutive and disturbing novel. The story is conveyed through the first person observations of Keiko Furukura, a woman in her mid-thirties who works in a convenience store in Tokyo. During her disconnected and occasionally violent childhood, Keiko concludes that “keeping my mouth shut was the most sensible approach to getting by in life” (11). Upon coming of age, she finds herself completely uninterested in the normal pathways to success in Japanese society. Eventually, she starts working at a local convenience store, where she finally discovers a sense of belonging:

I looked around and saw a man approaching with lots of discounted rice balls in his basket. “Irasshaimasé!” I called in exactly the same tone as before and bowed, then took the basket from him. At that moment, for the first time ever, I felt I’d become a part in the machine of society. I’ve been reborn, I thought. That day, I actually became a normal cog in society. (20, emphasis hers)

The rest of the novel is a sharp meditation on personal identity, social acceptance, the concept of normality, and self-commodification. Keiko’s infatuation with workplace procedure allows her to fabricate a scarily serene identity. She absorbs the mannerisms of her coworkers, studying them with sociopathic attentiveness in order to present as a normal person. Her greatest comfort is the store itself, “a forcibly normalized environment where foreign matter is immediately eliminated” (60).

Keiko has a few friends and keeps in touch with her sister and parents, but her social life is dominated by trying to ignore or sidestep her unconventional lifestyle. Unable to check the boxes that confer social acceptance––romantic exploits, career path, family plans––she struggles to find a comfortable niche from which to generate meaningful relationships.

Into this picture slouches a young cretin named Shiraha. This incel-in-training is obsessed with oversimplified interpretations of evolutionary psychology, blaming all of his problems on his inability to enact “Stone Age” schemas of gender roles. But he makes a good point now and then, highlighting the problem that has hampered Keiko her entire life:

You’re a foreign object. It’s just nobody bothered to tell you because they find you too freaky. They’ve been saying it behind your back, though. And now they’ll start saying it to your face too…People who are considered normal enjoy putting those who aren’t on trial. (122-3)

In a mutual effort to avoid seeming strange, Keiko and Shiraha form the least romantic cohabitation arrangement imaginable. Their interpersonal dynamics are odious, and yet the external world begins to accept and celebrate them. Keiko learns this primarily from her sister’s reaction to the news that she has a live-in boyfriend:

She’s far happier thinking her sister is normal, even if she has a lot of problems, than she is having an abnormal sister for whom everything is fine. For her, normality––however messy––is far more comprehensible. (133)

Keiko’s ultimate incomprehensibility to others proves intractable, but she does achieve self-acceptance in a fashion that is either liberating or horrifying, depending on your point of view. After quitting her job and being separated from the convenience store for a few weeks, Keiko realizes that her only path to happiness is to fully abdicate her individuality and embrace her one true vocation:

I couldn’t stop hearing the store telling me the way it wanted to be, what it needed. It was all flowing into me. It wasn’t me speaking. It was the store. I was just channeling its revelations from on high…More than a person, I’m a convenience store worker. Even if that means I’m abnormal and can’t make a living and drop down dead, I can’t escape that fact. My very cells exist for the convenience store. (160-1)

The ambiguity of this conclusion is tantalizing and intelligent. Perhaps Keiko has capitulated to the mentality of self-commodification that global capitalism and her corporate culture have foisted on her. Or maybe she’s a stubborn weirdo willing to follow her bliss, even if it defies social expectations and leaves her vulnerable to ridicule. To me, she is both heroine and victim––a dead vacuum animated by corporate order, aware enough to bask in her regimented glory, and sure to perish when her working days are done.

Rating: 7/10