Review: Steve Peters’s “A Path Through the Jungle”

by Miles Raymer

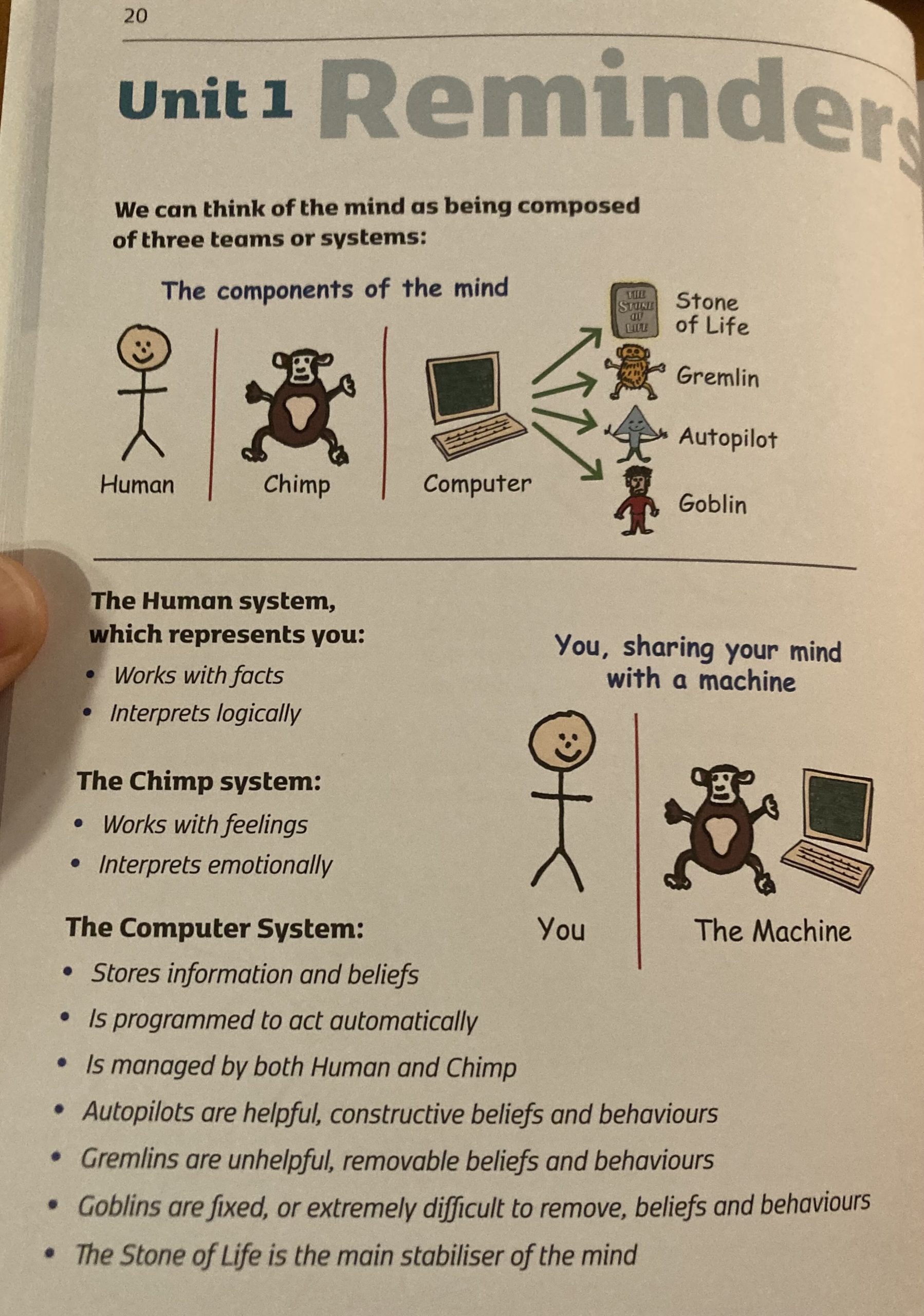

Steve Peters’s A Path Through the Jungle is a unique and valuable guide to self-understanding and self-regulation. The book is presented in seven “Stages,” each of which is comprised of “Units” that build on each other sequentially. The core set of ideas is what Peters calls the “Chimp Model,” summarized in this image from Unit One:

Throughout the book, Peters consistently sticks to the components of his model, demonstrating how they function in a variety of circumstances ranging from purely internal experiences to interactions with others. The most attention is given to the relationship between Chimp and Human, with many strategies for how to remain in “Human mode” during challenging moments and manage the Chimp in a healthy and respectful fashion. Peters also provides advice on optimal ways to program the Computer, including how to identify, remove, or work with Gremlins/Goblins (i.e. cognitive distortions), as well as how to consistently install helpful Autopilots. Crucially, Peters argues that the Human needs to intentionally program (or reprogram) the Computer in the wake of a significant event; this process drives learning, growth, and self-improvement.

One potential downside of the Chimp Model is that it’s a gross oversimplification of how the mind actually works. This is true, but it’s also true of every other model of the mind. The relevant question, therefore, is whether the Chimp Model is (1) a fair representation of how the mind works, and (2) a useful and healthy way of thinking about what it means to be a human. I don’t know enough about modern neuroscience to say definitively that the Chimp Model is a fair representation, but Peters includes many “Scientific Points” boxes that explain his ideas using the language and concepts of neuroscience. The book also includes nearly 500 citations, giving confidence that Peters has done his homework.

Regarding the question of whether the Chimp Model is a useful and healthy one, I feel confident that it is, with perhaps a few minor caveats that I’ll share below. If I had to sum up this book in a single word, it would be “practical.” Peters makes a laudable effort to ground his model in the problems of everyday life, to the point where a significant portion of the text is devoted to examples that show how the model can influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in real-world scenarios. His recommended Autopilots and rules for the “Stone of Life” put an appropriate emphasis on articulating our core values and then identifying specific attitudes and actions that can help us live in alignment with those values.

There were also several great terminological takeaways that I’m sure will stick with me. I enjoyed Peters’s description of the relationship between “commitment” and “motivation” and how committing to something keeps us invested even in moments when motivation is low. Another good one was the distinction between “reasonable” and “realistic” expectations, where developing realistic expectations based on facts is usually better than expecting the world to meet our definition of “reasonableness.” I also appreciated Peters’s explanation of how emotional “suppression” differs from “repression,” with suppression being a conscious and healthy way of tabling emotions in moments when dealing with them isn’t appropriate, and repression being an unconscious and unhealthy way of denying the existence of unpleasant or unwanted emotions.

Additionally, there are many passages showing how we can utilize basic mindfulness skills to not immediately identify with intense emotions and stay in Human mode. As Peters says: “Respond to situations; don’t react to them” (385). I give him credit for clearly stating that we don’t have to engage with or validate all emotions that arise for us––not always a popular opinion among psychologists these days. I’ve personally come to believe that cultivating the ability to reject certain emotions at certain times is a very useful and healthy skill. But it can be overused so needs to be complemented by other emotionally intelligent self-regulation strategies.

In general, the Chimp Model lines up with what I’ve learned about mental health since I decided to become a therapist about five years ago. Even though Peters is working with his own self-created terms and concepts, the model resonates with core ideas from many of my favorite therapeutic modalities, including Existential Therapy, Humanistic Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Narrative Therapy, and parts work.

That said, there are a few critiques I’d like to mention. One quick note is that readers who don’t like images or bullet lists will probably want to avoid this book. I found the format lively and refreshing, but it’s certainly not your typical nonfiction chapter book.

My other concerns are mainly based on ways that I anticipate readers misinterpreting the model rather than problems that are inherent to the model itself. For instance, a superficial examination of Peters’s work might lead someone to believe that he is “anti-emotion” and his model is all about caging the Chimp and preventing it from having any power within our internal systems. On the contrary, Peters consistently shows immense respect for the Chimp and goes out of his way to acknowledge its crucial role in alerting us to danger and keeping us in touch with our emotions. Much of the book is devoted to helping the Human learn how to compassionately listen to the Chimp and meet its needs.

Another possible misinterpretation would be to paint Peters as being against negative or unpleasant emotions. It’s fair to say that he does focus a lot on minimizing negative emotionality and eliminating it when possible, but I don’t think Peters takes this too far. Some elements of his model do conflict with frameworks that promote acceptance of negative emotions (e.g. ACT) rather than treating them as a problem to be solved. While Peters does fall more into the “problem to be solved” camp, he also regularly points out that acceptance of things we cannot change is a cornerstone of mental health. Practically, I’ve found that both of these approaches can be useful. Some people benefit from attempting to reduce or remove negative emotions from their lives, and others flourish via the path of acceptance. Many people, including me, use both methods. As with most aspects of mental health, it’s just a matter of experimenting and discovering what works best for each person.

A Path Through the Jungle delivers on its promise to help readers understand their own minds and develop tools to manage their internal and interpersonal lives. Peters’s model is genuinely novel, empirically-sound, accessible, compassionate, and fun! It’s hard for me to imagine someone engaging with this book and not taking away at least a few fresh ways to improve themselves, and for some readers it will offer transformational potential.