My Life as a Shepherd’s Dog: Iron & Wine’s Masterpiece Turns Ten

by Miles Raymer

Introduction

In fall 2007, I was beginning my sophomore year at the University of Oregon. Having made it through the growing pains of freshman year, I had begun to relax a little. I’d found a great group of friends to live with, and finally felt ready to embrace the college persona that made the most sense to me––a bookish ultimate frisbee player who preferred to stay in and get stoned with his housemates on Friday night rather than crash house parties or stagger through the streets of Eugene looking for love. I was still a sophomore, and plenty sophomoric, but I could see the kind of identity I wanted on the horizon; it was enough to keep me curious and motivated.

I was also experiencing what hindsight has revealed to be my life’s most intense period of musical discovery. It was a dynamic era for the music industry. The digital music economies––legal and otherwise––were still relatively new. Streaming services like Spotify didn’t exist, except perhaps in the clever minds of a few soon-to-be entrepreneurs. I’ve never used illegal downloading sites, so I still bought a lot of CDs back then, and also learned how to use thumb drives to trade music files with friends. The tunes didn’t flow as easily as they do now, but we were getting there. This environment jived wonderfully with my newfound habit of using cannabis to stimulate my post-adolescent, pre-adult brain.

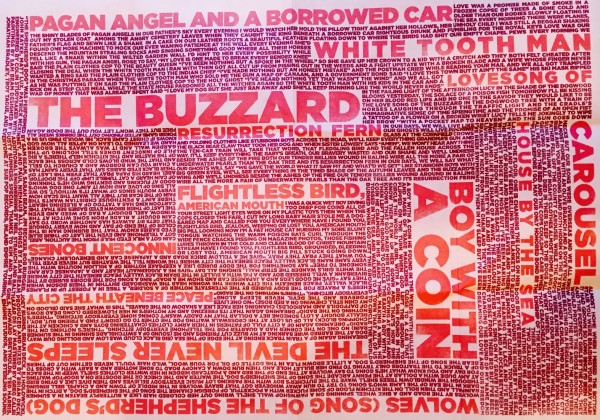

Onto this stage swaggered Iron & Wine’s The Shepherd’s Dog––an album that forever changed my relationship with music. Released on September 25th, 2007, The Shepherd’s Dog was a distinct departure from Sam Beam’s previous work. Beam had traded the hushed, acoustic tones that beguiled early listeners for a denser, big-band sound that put off some of his most devoted fans. But I thought it was perfect. Like me, Beam seemed eager to evolve in new directions.

In that year and those that followed, I listened to The Shepherd’s Dog countless times. Among the many artists and albums that captured my imagination, it always occupied a special place. This was due to the relationship I developed with the album, which became more complex and clearly-defined over time. Though Beam’s lyrics are famously non-literal, I always received a distinct political message from The Shepherd’s Dog––one that gave voice to my feelings about coming of age in the Bush era. Those difficult years seemed offset to some degree by Obama’s rise, but now, in the age of Trump, my relationship with this album has once again become unpleasantly relevant. A decade is a long time in dog years, and it seems that the wisdom inherent in this particular canine has only become more potent.

In this essay, I will argue that The Shepherd’s Dog represents a haunting examination of the morally-compromised position occupied by 21st-century middle-class Americans. We are not sheep, but neither are we shepherds. We are shepherd’s dogs.

A Note on Method:

Anyone who has thought critically about art knows it is a fool’s errand to argue that a piece of art definitively “means” something; that is not what I am up to here. I am using someone else’s art to creatively explore my feelings about my national and political identity. The arguments are parochial insofar as they are rooted in my experience of listening to this album not just as an American in general, but as the particular type of American I find myself to be.

I am incapable of intelligently commenting on the musical production or composition of these tracks, but I will say that The Shepherd’s Dog is as good a piece of music as I’ve ever heard, and better than most.

For this essay, I’ll stick to an analysis of the lyrics, treating The Shepherd’s Dog more like an epic poem than an album. I’ll also narrow my focus to a particular line from each song that especially speaks to my interpretation. At each turn, we shepherd’s dogs are caught in conundrums of injustice, ones we are complicit in perpetuating even if we remain unaware of their existence.

I. “The Pagan Angel rose to say, ‘My love is one made to break every bended knee…'”

The Shepherd’s Dog is an album deeply concerned with the loss of divinity. The songs are filled with references to Biblical characters, the language of prayer, and worldly idols. Were I a religious person, I’d probably think Beam was lamenting the absence of religion in modern life. But my secular interpretation is a bit different, and is perhaps best captured by this passage from Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus:

Modernity is a surprisingly simple deal. The entire contract can be summarised in a single phrase: humans agree to give up meaning in exchange for power. Until modern times most cultures believed that humans played a part in some great cosmic plan…[But] to the best of our scientific understanding, the universe is a blind and purposeless process…We are constrained by nothing except our own ignorance…No paradise awaits us after death––but we can create paradise here on earth and live in it forever, if we just manage to overcome some technical difficulties. (200-2)

It is this exchange of meaning for power that I observe Beam wrestling with in The Shepherd’s Dog. Despite the technological marvels of the globalized economy, modern medicine, and the Internet age, the prospect of overcoming ignorance and the other “technical difficulties” that stand in the way of paradise on Earth seems dimmer by the day. The Shepherd’s Dog beckons us into a world where the exchange of meaning for power has already taken place, but the exchange has resulted in tragic outcomes: environmental degradation, mass poverty and hunger, gross wealth inequality, the sixth extinction, globalized slavery, widespread anomie, extremism of all stripes, weapons of mass destruction, and climate change. With the “Pagan Angel”––our benevolent and vengeful shepherd of modernity––on the rise, the human power that ought to be building paradise on Earth is instead an agent of plunder and exploitation.

We shepherd’s dogs are caught up in this mess, just like everyone else. But we are privileged in that we are the chosen servants of the Pagan Angel. We guard the kingdom but do not rule it, maintaining order not with conscious care, but rather by force of habit and blind faith. Any desire we may have to flee from this obligation falters when we realize that balking the master too many times will compromise our own chance to flourish. So we stay put, we work, we run, we eat, we sleep, we fuck, we die.

I cannot avoid bending the knee to the Pagan Angel of modernity, even if I know it will break me. Thus, begrudgingly, I have become a shepherd’s dog. Or, more accurately, I’ve realized that I was one all along.

II. “And we all got sick on a strip club meal…”

This line from the second track of The Shepherd’s Dog brings to mind a chronic American crisis that I’ve watched with dismay over the last decade: the crisis of nutrition. The diets of most Americans are dominated by “strip club meals” of inexpensive, processed foods that are scientifically engineered not to satiate our hunger, but rather to make us consume more calories. As a result, America has given birth to the first generations in history to experience health problems from an excess, rather than a dearth, of calories. Incalculable suffering is also experienced by animals in factory farms––the least fortunate victims of this system.

All Americans must contend with nutrition-delivering systems that do not prioritize our health, but we do not all fight this battle on equal terms. There is a tripartite socioeconomic problem here that involves the cost of food, access to food, and the psychological capacity to have a positive relationship with food. Shepherd’s dogs have a huge advantage in all these areas. We have the money to buy healthy food, live in towns and neighborhoods with grocery stores that source and sell local produce, and sometimes even grow significant portions of our own food. We also tend to have enough leisure time to cook for ourselves and participate in cultures of healthy consumption.

Lower- and working-class Americans, on the other hand, struggle on all these fronts. Not only do these folks have less money and less access to good nutrition, but they also have less leisure. If the daily grind is so challenging and exhausting as to leave someone desperate to feel good about something (anything), then a cheeseburger and milkshake can be the surest route to a quick pleasure response. People who undergo continual stress find it more difficult to develop and maintain healthy eating habits. So, as in every other aspect of American life, the poor have the greatest disadvantage.

The ugliness of being a shepherd’s dog in this scenario is plain. Acting in our perceived self-interest, we restrict our experience of food to liberal enclaves peppered with co-ops, community-supported agriculture, and farm-to-table restaurants. From tables piled high with “real” food, we smugly decry factory farming, monocropping, and GMOs. The least we can do is admit that our experience of healthy nutrition is a privilege from which many Americans are cut off.

III. “No one is the savior they would like to be…”

Although I didn’t take the issue seriously until after leaving college in 2010, I’d been vaguely aware of climate change throughout my youth. Both of my parents have been environmentally-conscious for as long as I can remember, so I was brought up to think carefully about my consumption of public resources. Despite my father’s native cynicism, those early years were characterized by a general optimism that common people could help overcome the problem. “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” campaigns echoed through the hallways of my junior high school, and my Dad started riding his bike to work while Ma bought a Prius. If we concerned citizens educated ourselves and adjusted our lives accordingly, surely we could become the “saviors” of the planet!

This notion has since been revealed as something between a half-truth and an outright falsehood. The warming of the planet is driven mostly by large-scale, industrial carbon consumption. Individuals and small communities can forsake carbon entirely, but it won’t make a significant difference if industry is allowed to continue as normal. And every time someone checks out of one aspect of the carbon economy, hundreds of less fortunate citizens of the world are clamoring to step in and consume more in pursuit of the plastic-planed, gas-guzzling good life.

The national and multinational corporations that burn the most carbon are subject only to the laws of nations, and even that is a shaky proposition. More and more, they utilize their vast wealth to inject ambiguity into climate policy discussions and prevent new, better laws from being passed. Most climate scientists and advocates still hedge their warnings using phrases like “if we don’t do something very soon,” but my creeping suspicion for the last several years has been that the window for truly effective climate action closed decades ago. I now believe that the best case scenarios are no longer on the table, and future generations are destined to experience unprecedented degrees of suffering.

Despite encouraging signs of a sustainable energy revolution on the horizon, oil remains the Pagan Angel’s anointed champion. With his guidance, we shepherd’s dogs have developed a taste for it, and lap it up at ever-increasing rates. The fire that burns the world is the foundation of our prosperity.

IV. “But our sons were overseas…”

I’ll never forget a lecture I heard in college by Cheney Ryan, a social and political philosopher who teaches at the University of Oregon and Oxford. He argued that one of the most dangerous developments in American history was when we abolished the military draft after Vietnam in 1973. Until that moment, I’d always considered the absence of a draft to be one of the great achievements of my society. I’d read books like Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, which made the draft seem like one of the most terrifying experiences a generation of young Americans could endure.

But Ryan completely spun me around on this. He said that having a draft is actually healthier than not having one for a society such as ours. If a nation is going to send its sons and daughters overseas to fight, those bodies should be impartially chosen from all walks of life. Even when fighting an unjust war, this dynamic can create a sense of communal sacrifice and unified national identity. More importantly, it can also give birth to widespread protests that might force the government to reconsider its priorities. Even though there was always a rarefied elite that could escape it, the institution of the draft ensured a collective concern with how America’s military might was wielded.

Abolishing the draft changed all this. The Pagan Angel realized that he could fight his forever-wars without having to deal with all those pesky protestors, kids with a future who didn’t want their lives senselessly blotted out in some jungle or desert halfway across the world. Let them continue on their path; they will make excellent shepherd’s dogs. Meanwhile, let’s allow wages to stagnate for almost a half century and stop funding education for the poorest Americans, creating a permanent underclass from which to extract our fighters. Then we sidle up to their crumbling schools and decaying towns with a friendly proposition: give me your body, and you too will perhaps be a shepherd’s dog one day.

America has been at war my entire adult life, and I can scarcely name a family member or close friend who has been involved in or seriously affected by our foreign conflicts. Meanwhile, there are towns across this country filled with families who have been emotionally, psychologically, and physically broken by their “best shot” at the American Dream.

V. “I’ve been living to run where they’ve led…”

The notion that people are and ought to be free to make their own decisions is a cornerstone of modern civilizations in the western world. The governing structure of liberal democracies contains the implicit assumption that citizens are free to choose their political perspectives and exercise them according to preference and self-interest, and those of us raised in liberal democracies tend to uncritically accept the idea that societies in which individuals can maximize their personal freedom and economic potential are necessarily the best societies.

We Americans have a peculiar devotion to the idea of freedom, one that is extreme compared to that of other developed western societies. It stems from our history of rebellion against empire, from our blood-drenched theft of North America under the guise of Manifest Destiny, and from our rise to global economic and military dominance after World War II. No other country sees itself as so proudly populated with self-made, get-it-done, free-wheelin’ cowboys who don’t need a lick of help from the government or anyone else.

Our fetishization of freedom may very well cause modern America to be remembered by later generations as the apogee of human hubris and idiocy. Modern science offers no support for the idea that humans possess any sort of radical freedom divorced from the same causal mechanisms that determine the behavior of nonhuman animals, plants, or other constituents of the natural world.

It gets worse for proponents for free will, because it would seem that not only are we not radically free in the sense of being able to do anything we please, but also that we may not be free in any sense at all. The last half-century has seen larger leaps in our understanding of the brain and psychology than in any previous era, and evidence for free will is tough to come by. This is not to say that determinism is absolutely true, but just to say that the evidence points in that direction. It is the same line of thinking that allows me to say that I’m almost entirely certain there is no God, not because I can prove God’s nonexistence but because there is no credible evidence supporting God’s existence.

Given that the phenomenological experience of free will, responsibility, and guilt are bedrocks of our evolved psychological and social systems, it is no surprise that most people are either unable or unwilling to accept the nonexistence of free will. It does not feel good to be told that you’ve “been living to run where they’ve led,” especially when the “they” in question are the laws of physics––predetermined rules that care nothing for human joy or suffering, that we did not have any role in creating, and have no hope of changing. But science indicates that this is increasingly the only empirically-responsible interpretation of the human condition. The jury is still out regarding the moral and societal consequences of people accepting determinism en masse, but there’s no doubt about the gravity of those consequences, especially when applied to our justice system.

I’ve spent a lot of time wrestling with this problem, and while I consider myself a hardline determinist, I’ve also had to accept that assuming such a philosophical position will not release me from the experience of personal and social responsibility for my actions or the actions of others. In non-sociopaths, the intellect cannot override our evolved emotional reactions to human behavior. The intellect is quite capable, however, of eviscerating the justifications we muster to legitimize those reactions. The resulting paradox––that I can’t escape holding myself and others accountable even though I view accountability as a fraudulent idea––often leaves me paralyzed. And it is in that fearful quiescence that the Pagan Angel soothes me with false promises of liberation.

VI. “God knows if Christ came back he would find us in a poker game, after finding the drinks were all free but they won’t let you out the door again…”

Perhaps the most tumultuous change in the last decade has been the rapid rise of social media, which now dominates American culture with unprecedented influence. Given the newness of this technology, it’s hard to say anything definitive about what it’s doing to us or where it might lead. But there’s no doubt that social media has precipitated a sea change in how Americans think about privacy, community, and truth.

Many users of social media do not understand that these services are not “free” in the strict sense of the word. Sites that do not charge a fee sell data about the online activities of users to advertisers, who then target ads according to what the data tells them we will be likely to purchase. This is why the ads on Facebook or the side bar of Gmail are sometimes strangely catered to your particular interests, or why a product you searched for online yesterday may appear in your news feed today.

Though I can understand why many people are bothered by this business model, “big data” is not an issue that keeps me up at night. In fact, I think big data will be the key to groundbreaking progress in fields such as health care. And honestly, I don’t care that someone could theoretically acquire a list of all the pornography sites I visit, or my Google searches. This shepherd’s dog is happy with his free drinks.

I wish my feelings about social media stopped there, but unfortunately there is a much darker side to this shift in the American digital landscape. In the wake of the recent election, it has become clear that social media is a perfect mechanism for obfuscating fact, manipulating voters, creating impermeable echo chambers, harboring hate, and promulgating lies. This is the part of the social media “poker game” that I’m afraid we can’t escape. Many people do not use social media as a tool to strategically improve their lives, but rather become duped by those who design or learn how to game social media for their own ends.

There is still a surfeit of terrific journalism and research being conducted throughout this country, but it does not seem to be reaching the people and places where it could have the biggest impact. Increasingly isolated online communities are circling the wagons around their chosen ideological positions, happy to chant the same slogans ad nauseam while mocking and dehumanizing dissenters. And it’s not just online; plenty of Americans are also physically sequestering themselves in regions, cities, and neighborhoods packed with like-minded and like-looking people. I’d love to say this is a more serious problem for the political right than for us lefties, but I’m not in the fake news business. That’s the Pagan Angel’s wheelhouse.

VII. “Song of the shepherd’s dog, a ditch in the dark in the ear of the lamb who’s going to try to run away…”

This is the line from The Shepherd’s Dog that first inspired my interpretation of the album. The song is titled “Wolves (Song of the Shepherd’s Dog),” and in my reading, it’s all about the fraught project of maintaining order when wolves begin to close in on a herd. Every civilization, no matter how robust, has certain wolves––pressure points that can trigger collapse. The closer the wolves, the more pressure the Pagan Angel is under to convince his sheep––and his dogs––that everything will be fine.

While the most obviously lethal wolf circling the American herd is global climate change, its jaws are not yet at our throats. I believe the more proximate threats are racial tensions and identity politics. Our brutal legacy of slavery is that “ditch in the dark” always waiting to trip us up, a sin so profound that we may never extirpate it from our national psyche.

Modern America is a testament to the reality that historical blunders can have consequences that last for many generations and centuries; we have a very, very long road to travel if we want to truly overcome this heritage. The phenomenon of identity politics––a frustratingly mercurial term––has both enabled and hindered progress. There is no doubt that identifying people based on race can be both necessary and beneficial to begin righting the wrongs of the past, but it is also true that race is a completely constructed concept with no serious basis in biology beyond superficial differences. Dividing the American population up into categories and subsets of more or less privileged people is a project with limited uses, and can sometimes create more problems than it solves. (For anyone eager to explore just how complex and divisive this issue has become, I recommend this exchange between Mark Lilla and Lovia Gyarkye.)

We shepherd’s dogs are 21st-century overseers obliquely charged with keeping the Pagan Angel’s sheep in line. Our indirect connection to the oppression we perpetuate is far less intimate, and therefore more insidious, than that of the overseers who stalked and tortured in the cotton and sugarcane fields of centuries past. I truly want my country to be a better, safer home for nonwhite Americans, and I support gradual, systemic changes that would steer society to that end. But my desire for progress has limits; justice does not enjoy my full allegiance. I am too dependent on the Pagan Angel to seek radical change, too beguiled by the fruits of my chosen status, and too fearful of the wolves that will come for me when the sheep have all been slaughtered.

VIII. “When Sister Lowry says ‘Amen,’ we won’t hear anything…”

Recent research has shown that my generation is less religious than any previous generation. And while that’s music to the ears of this atheist dog, I have reservations about the current viability of American communities in which religion plays little or no significant role.

This has nothing to do with religious ideas or teachings being inherently valuable, and everything to do with religion’s place in human history as a particularly effective form of social glue. Our social networks––religious and otherwise––depend utterly on large groups of people believing in fictitious ideas such as money, nations, or gods. Traditionally, religion has dominated this fiction market, and has therefore been an incredibly useful tool for promoting social organization and perseverance. But, as any reader knows, some fictions are better than others. Most modern religions are not only founded on ideas that are anathema to a scientific understanding of reality, but have also been utilized as justifications for countless unjust practices, governments, and conflicts.

It is wonderful to see my generation actively turning away from the intellectual tripe that passes for good sense in most houses of worship, but it would be foolhardy not to worry about what we are turning toward. Most distressing is the suggestion that we are turning toward nothing at all––a vacuum devoid of morality and meaning whose only logical conclusion is nihilism. The Pagan Angel would like nothing more than for his dogs to be consumed by such affectations; it makes us easier to control.

While I do not think the majority of nonreligious Americans embrace nihilism, I do think we have largely failed to recognize and respond to the loss of ritual and community that secular life usually entails. All superstitions aside, people need to feel that they are part of something greater than themselves. Until we can find a way to engineer this impulse out of human nature, we will be stuck with it.

Nonreligious Americans need to take seriously their need for belonging, for habitual forms of supplication and worship, and for communing with the great unknown mystery of the universe. And recognizing those needs isn’t enough; we also need to create and maintain institutions that carve out time and space for nonreligious rituals and values to be properly honored. Without taking this next step, we will never be able to offer a suitable sanctuary for the increasing numbers of ideological refugees desperate to forsake the religions of the past.

IX. “God made her eyes for crying at birth…”

Even in this era when the power of religion seems to be on the wane, American culture is steeped in religious symbolism and ideology. One of the most persistent and spurious myths propounded by religious teachings is the assertion that men and women are “designed” by God to enact certain sex-specific roles and behaviors. This issue is made thorny by the biological reality that there are indeed differences between the bodies and minds of men and women, but too often these subtle distinctions are misrepresented as justifications for whatever sex-essentialist argument someone is using to press a cultural, economic, or religious agenda.

This problem is particularly difficult when applied to the issue of childbearing. In a country where huge numbers of women still do not have access to appropriate health care, including abortion and birth control, we celebrate reproduction as an unalloyed good. We nonreligious folks are just as guilty of this as those in religious communities, although we don’t tend to package our zeal with quite as much wackiness. But who could blame us? Even without religious window-dressing, the biological imperative to have children is as strong as (or stronger than) any other human impulse. Replication is the engine of evolution, the bedrock of humanity’s endurance.

While this may be true in a historical sense, it certainly is not true of the modern moment. Here, now, global overpopulation is a serious concern, one that our atavistic habits are not good at acknowledging. At current rates of consumption, we would need multiple Earths to provide our current population with the kind of lifestyle enjoyed by shepherd’s dogs. The Pagan Angel is mighty, but may not be up to the task of conjuring extra planets from which we can extract resources.

I wish it were socially and politically acceptable to speak frankly about the need to reduce the global population and humanely restrict reproduction. Making this shift would liberate everyone, and women especially, from the obsolete notion that having children is somehow more important than choosing not to have them. Over time, it might also force us to embrace new economic models that do not depend on endless growth in order to remain financially viable. Parenthood is one significant source of human meaning and happiness, but should not occupy a position of privilege over other sources.

X. “Everybody bitching, ‘There’s nothing on the radio…'”

Without a doubt, Americans consume more media than any other group in human history. Starting with books, radio, and cinema, then progressing to television, video games, podcasting, and the first glimpses of truly immersive virtual reality, the last century has generated a bottomless cornucopia of eye and ear candy. We are completely awash in easily-accessed experiences that compete for our attention and our dollars.

I’ve come to see these glorious distractions as the single most powerful element of control in the Pagan Angel’s inimitable toolkit. My idea of utopia is “story time all the time”––a life where all material needs are met and people are free to either create or consume media all day every day, either solo or in any conceivable number of social permutations. This is a great image for a post-scarcity society, but of course that is not what I am living in. Perhaps it is an instance of tragic timing, with human civilization discovering the technological playground of post-scarcity living prior to generating the practical means of sustaining itself indefinitely.

One of the most surprising aspects of our new relationship with media (and other aspects of life) is how tough it becomes to choose when the possibilities are endless. I can’t count the number of times I’ve scrolled through inexhaustible lists on Netflix or Amazon, bitching that there’s nothing decent to watch. But do I walk away and find something better to do? Usually not.

The hard truth is that media prevents shepherd’s dogs from confronting and overcoming the calamities poised to bring down the walls of the Pagan Angel’s kingdom. Why take to the streets to insist on a global carbon tax when the season finale of Game of Thrones is airing in five minutes? I suspect we’ve reached a point where meaningful change will only be precipitated when political and/or physical climates become so hostile that we are forced to put down our screens and fight for survival. I also suspect that there won’t be much worth saving by that time.

XI. “Give me…”

“Peace Beneath the City” is the penultimate offering on The Shepherd’s Dog, and probably my favorite track. This isn’t because I think it’s necessarily the best, but because of an experience I had seeing Sam Bean perform it at the McDonald Theatre in Eugene. This was probably in 2007 or 2008––I can’t remember the exact date.

It was my first time seeing Iron & Wine, and I was lucky to catch one of the shows he did solo, just him and a couple acoustic guitars. I’ve seen him perform with big bands as well, and while both types of shows have their own appeal, I don’t think anything compares to seeing Beam perform solo. When it came time to perform “Peace Beneath the City,” Beam asked everyone in the theater to clap the simple rhythm that anchors the studio recording of the song. First we wanted to go too fast, so he had to slow us down a bit, but he stuck with it and we eventually figured out the right pace. What followed was one of the most mesmerizing live music experiences I’ve ever had. Something about the low-tech, tribal nature of providing that steady rhythm while Beam played and sang proved utterly transcendent. It was as perfect a moment as I’ve known on Earth.

From a lyrical standpoint, “Peace Beneath the City” is a distinctly disturbing song. It drips with imagery of decay and abandonment, finding its center in a series of dark supplications to the Pagan Angel:

Give me good legs and a Japanese car and show me a road…

Give me a juggernaut heart and a Japanese car and someone to free…

Give me a yellow brick road and a Japanese car and benevolent change.

It is especially telling that any desires for something beyond material or bodily gratification, such as “someone to free” or “benevolent change,” come only as afterthoughts that take a backseat to more “important” needs. This ordering of personal priorities captures perfectly the mindset of a shepherd’s dog, whose first world problems provide a constant distraction from the instantiations of true suffering through which the dog wanders.

XII. “Lost you, American mouth, big pill stuck going down…”

The last track on The Shepherd’s Dog is famously enigmatic. Winding through a lilting labyrinth of loss and discovery, Beam seems content to let listeners take what they want from this euphoric sendoff.

For me, it all comes down to the song’s last line––this image of the “American mouth” choking on a “big pill.” Someone who is choking has no voice, and perhaps no future. To be a shepherd’s dog in today’s America is to be silenced by a cacophony of unchosen consequences, to be imprisoned in cycles of fleeting ecstasy and lingering despair, and to experience the responsibility for progress as so diffuse that it becomes meaningless. It is to bend a broken knee to the Pagan Angel, our great source of salvation and sin.

Postscript

Dear Reader:

If you made it this far, I owe you a hearty thanks as well as an apology. When I began this essay, I had no intention of making it either as lengthy or as grim as it turned out to be. This is not an easy or a fun read. I do not expect many people to bear with it.

I fear this is the part where I am supposed to try to make us all feel a little better. I ought to offer up the possibility that the Pagan Angel is actually the shepherd leading us all to utopia, or claim that the Angel’s reign is slipping and will soon be replaced by a better world order. And while I’m not quite arrogant enough to reject those suggestions outright, I will not endorse them. I will endorse––now and forever––the incredible work of Sam Beam and the other good folks who helped bring The Shepherd’s Dog into the world. This essay is dedicated to them, and also to all the other artists out there trying to examine and improve the experience of being human at this moment in time. These people are heroes; I could not begin to guess how many lives they’ve saved.

The plain truth is that 2017 has not been a good year for my feelings about being a person in this world. It has not been a good year for the side of me that believes humankind can and will overcome the obstacles that stand between us and lasting, ethical prosperity. If we do still have a chance of realizing that world, I believe that time will come only after a period of turmoil and suffering that is unlike anything our species has previously endured. This period is already the one and only reality for millions of people across the planet, and is swiftly coming for the rest of us.

Self-expression is the only medicine I’ve discovered to effectively combat the onslaught of melancholy. This essay is an attempt to uncover the source of that sadness, to explain to myself why I have started feeling so guilty about the nature of my privileged position on this planet––a position for which I am immeasurably grateful but have done nothing to deserve. I should point out that the idea of being a shepherd’s dog focuses primarily on the morally fraught aspects of my political identity, and does not therefore represent a comprehensive assessment of my political actions or perspectives. Nevertheless, the power this metaphor holds over me is immense.

I sincerely hope that this essay might give voice to the struggles of those who may come across it. If any of the ideas or emotions expressed here ring true for you, then you can know with certainty that you do not bear those burdens in complete solitude.

Wow Miles. I’m humbled and grounded by your words: I see you. I don’t know what exactly shifts when I center in quality of heart you call out here, but I feel that it is something vital to bleed in the open, alone and with others.

Thank you for the offering of your struggle.

Hey Mark! Thanks so much for taking the time and for the kind words. Glad you seemed to get something from this. I really appreciate your readership!

Well I made it all the way through – and it was a mind boggling read. My generation has so thoroughly muddied the waters for your generation and I must shoulder some of the responsibility. It is painful to know how this deeply divided and chaotic world has influenced you, but then I also have great faith that you have the intellectual and emotional skills to navigate what comes your way. Thanks for this glimpse into your thoughts …

Thanks for reading, Ma! I don’t think the baby boomers should be held entirely responsible for the mess America has made of itself. A lot of the moving parts were already in place long before you came along! The “cacophony of unchosen consequences” is something every generation must face. I certainly think folks like you have done more than your fair share to battle what history may reveal as a virtually unstoppable downward spiral.

As insightful as it is dark, this piece of writing is evidence of your deeply felt connection to the pain of the world.

I will not insult your intelligence by feeding you the pablum my parents generation fed us — that every generation has its share of crisis and suffering, its cross to bear. When we raged at the reelection of Richard Nixon in 1972 and what we knew would mean the continuation of the Vietnam War, when we feared in 1980 that the election of Ronald Reagan would bring nuclear Armageddon on our heads, when we wept at the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia — there was little comfort and solace to be found in the idea that every generation has its cross to bear.

I share your conviction that the remaining course of human history will be both short and brutal beyond anything imaginable. Your generation bears a cross of catastrophic magnitude and for that I am deeply saddened.

What is there but to humbly suggest that you search out moments of joy where you can and that you continue to rage against the “cacophony of unchosen consequences”.

Thank you for sharing your soul through your writing, Miles. It is a gift!

Thanks so much for this comment, Jim! I really appreciate you taking the time to wade through the piece and respond. I remain determined to seek and sustain moments of joy, and am fortunate enough to have already experienced more than my fair share of them in the short time I’ve been alive. You and the other amazing adults I grew up around provided many opportunities for growth and happiness, and for that I am very grateful.

I’ll keep writing, and I hope you’ll keep reading!

As always, Miles, your writing makes me energized and motivated, even while casting a sobering light on the world around us.

This essay also makes me particularly glad that we have been sharing ideas, conversation, and music for these ten years and more. You are a gift, and I am grateful to have the chance to examine our shortcomings and imagine potential futures with you.

Thanks so much, Katie! You are also a gift and I couldn’t be more grateful for your presence in my life. Hard now to remember what my brain was like before you jumped in there and started improving the scene.

Much love and thanks for reading!

This is important. In my mind, I draw parallels with Animal Farm, which I suppose is the point. But fascinating and well-thought out – thanks for publishing this!

Thanks very much for reading and leaving this comment. I am grateful that my words reached you wherever you are!