The Life and Death of Sweet Meats: A Tribute to Barry Snitkin

by Miles Raymer

This is my fiftieth journal, which feels like an appropriate time to reflect on the origins of the words&dirt blog. When I began this project more than two years ago, I wanted to develop ideas about a way of life that was experimental for me. I wanted to step outside the traditional channels of education and employment that had dominated the first part of my life, and create something different for myself and my loved ones.

All new endeavors owe a debt of gratitude to people and places that came before. In my case, I can trace the origins of words&dirt back to the three months I spent living with Barry Snitkin and Meadow Martell on their land in Cave Junction, Oregon. Meadow was a nurse who worked mostly from home, and Barry ran a one-man organic farm. They had been family friends as long as I could remember, and were all too willing to take in a floundering college graduate with a teaching degree he wasn’t eager to use. In exchange for help on the farm, Barry and Meadow opened their home and hearts to me. They also changed the course of my life.

When humans undergo periods of rapid emotional and intellectual development, we usually aren’t aware of what’s happening to us in the moment; after months, years, or decades, we have to look back in order to understand the scope of change. When I was living in Cave Junction, I thought I was killing time before taking a job with the JET Programme in Japan. I’d recently set my long-term sights on being a philosophy professor, so I figured I’d head to graduate school after my year abroad. To familiarize myself with my intended area of study, I spent half of each day reading about naturalized ethics, and the other half working in the garden. Barry and Meadow encouraged me in all my labors, graciously melding their quiet life with mine.

I always thought living in Cave Junction would be a good experience, but I could never have predicted that it would provide both the moral justification and the practical model for how I would live after Japan. I thought I was waiting for my “real life” to begin, but I was actually acquiring the habits and perspectives necessary for shaping a new life––one I would mimic at first and then slowly adapt to fit my personality and circumstances.

Here are some passages from my 2012 journal that represent this process:

March 12: There was a beautiful moment at lunch when Barry was smiling at me. He’s got a great smile, like clouds parting. He doesn’t hold anything back. But the best part was that we were eating open-faced sandwiches and he had sprouts and a few other bits of food stuck in his beard. It was just so genuine, so unaffected. It really shows how folks who live out here do so at a different pace, under a different sky.

March 15: It has been raining all day; the torrent has been ceaseless from the moment I woke up this morning. I dug another trench from the house out to the pod. It was wet, grimy, and wonderful. The methodical nature of this work coupled with the absolute exhaustion I feel after I’m done is so fulfilling. I finish tasks in a peculiar state of spent euphoria, a relaxed balance born from a long buildup of tension in my body.

March 16: When I was working earlier I had a few blissful moments where I realized that I wasn’t thinking about anything save the task at hand. And I definitely feel that way when I write, but I just can’t see a way to turn that into some kind of actual life where I can have any kind of security. Security. One of the most difficult and complex subjects of our time. National Security. Social Security. Financial Security. And when I say I have a problem it’s because of “insecurities” I have about one thing or another. I want to throw myself into something worthwhile, but I want it to spell out some kind of outlined path, some kind of definite end goal. But Jessie’s probably right again—if I didn’t have the time to think about all this I’d just feel trapped and be complaining about how I didn’t have time to think or space to breathe. This is one of the thoughts that makes me feel hopeless about the future.

March 18: While building raised beds today I was struck by the aesthetic of building, by the joy of using tools to create order, especially when a consequence of that order is sustenance. Specifically, the moment when a screw moves two planks of wood that almost imperceptible distance closer to one another. It’s like sex, when two people finally close that last gap and, at least in memory, become fused together forever. But it also struck me that all this order starts decaying the moment we set it in place. Entropy is immutable. We order things “for the time being,” or “as long as we need.” It is insulting to the rest of the universe to ask for more. After all, there are only so many atoms to go around.

Reading those last lines feels especially raw now. On December 21st of last year, Meadow called Ma with the news: Barry had been diagnosed with advanced colon cancer. This development was sudden and shocking for everyone who loved Barry, especially since he was generally one of the healthiest people you could meet.

After the New Year, Ma and I drove up to Cave Junction for the weekend. I’ve experienced a relative paucity of death among my immediate friends and family, so this was one of my first experiences interacting with a loved one whose life was slipping away. I tried to act like everything was normal, but it was difficult. Barry––a man known for his physical and mental vigor––was quiescent and shrunken. His words came quietly and with much effort. Meadow was overwhelmed but in remarkably good shape considering the circumstances. Ma and I alternated between visiting in the living room, cleaning the house, and tidying up the garden.

Working in the garden was the most difficult part for me. Everything felt out of place, myself most of all. My efforts to turn the compost pile and rearrange some errant hoses could not alter the pall of disorder and sickness that had settled over the land. Everything about that day was stark and cold, my hands nearly as numb as my heart.

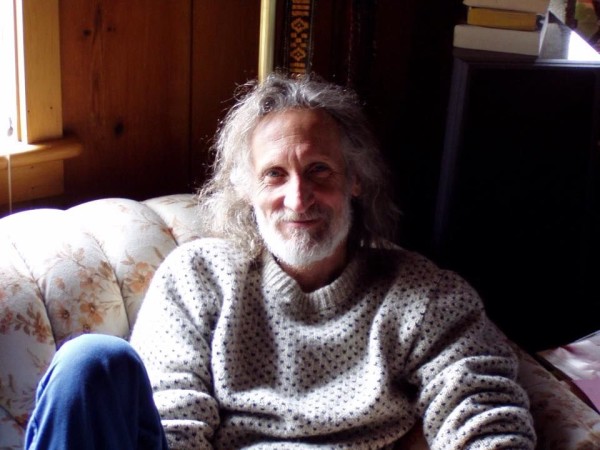

Before leaving, I gave my love to Barry, as well as a letter I’d written to thank him for being a part of my life. I also took this picture of him and Meadow to remember him by.

On February 5th––less than a month after I last saw him––Barry died peacefully at home.

It was only after Barry was gone that I realized just how little I actually knew about him. I’d asked him once about his past, but he wasn’t forthcoming with details. I knew he was an activist with a deep understanding of Southern Oregon’s forests and rivers, but the extent of his friendships and environmental activities only became apparent to me with the flood of support from loved ones during his sickness and the subsequent wave of grief at his passing. One eloquent obituary called him a “river sage” and mentioned his role as founder of the Siskiyou Film Festival. This man was a local institution, and felt somehow different from the Barry I’d known growing up.

When I think about Barry, I think of the way he expertly tended the fire in his living room, waiting patiently to add a new log at just the right moment. I think about how carefully he transferred his garden starts from the greenhouse to an outdoor bed, treating each plant like a delicate treasure. I think about his giddy face on the day we cracked a double-yolked egg from one of his hens. I think about his abhorrence of waste, and how ornery he would get if I used too much water to wash the dishes. I think about his frustration with governments and industries that compromise Earth’s great ecosystems. I think about how, seeing my love of reading, he urged me to pick up Bill McKibben’s Eaarth––the first book that made me think seriously about becoming involved in local agriculture.

All of these memories point to one conclusion: Through the mysterious alchemy of human relationship, many of the perspectives and experiences that made Barry who he was are living in me now, and in the many others who knew and loved him. This is the only kind of life after death I believe in.

I think Barry would be happy to know we still think about him, but he’d also want us to take action, to protect or nurture some part of the natural world. To honor his memory, my family decided to grow some sweet meat squash from seeds that Ma found in Barry and Meadow’s storage room. In April, I dug a couple beds for a dry-farming experiment, and we planted the sweet meat seeds.

We planted some other squash as well––delicata, acorn, butternut––but it won’t surprise anyone who knew Barry’s green thumb that his sweet meats outgrew them all. By fall, we had four big ones, which wasn’t bad for a dry bed with only a little compost added.

We ate one of the sweet meats shortly after harvesting to see how they’d turned out, and it was some of the best squash we’d ever tasted. We were biased by knowing the squash came from Barry, but I learned from him and Meadow that the personal element of food production often makes the difference between a good meal and a great one.

We saved the biggest sweet meat for Thanksgiving dinner. I cut it up, added some salt, pepper, and brown sugar, and baked it.

Before serving dinner, I made an announcement about the squash’s provenance, and asked each of our guests to think of someone, alive or dead, who helped nudge them in the right direction or discover a better path.

Nearly a year after his death, I am still discovering ways that Barry influenced my life. The three months I spent under his tutelage have played a critical role for me. I live now as I did then––as he did then––with a loving partner who supports me, my family close by, and a world of living things outside my door. Some of these things need my help, and some of them need to be left alone. I try not to confuse them.

In the rare moments that I happen to shed my identity and merge momentarily with the omnipresent miracle of nature, I sometimes find a wisp of Barry. Sometimes he’ll announce himself with a sunrise,

or a moonset,

and I’ll glimpse him again, coursing through the veins of a world he so dearly loved.

Helping people see the world this way is one of our most sacred duties––one that Barry assumed with astounding ease and deepest sincerity. He was taken from us by the most natural of events: the great Harvest that comes for us all. But only through the act of harvesting can we discover the seeds of tomorrow.

As usual well done food bits for my hungry ghosts!

A friend of Barry and a fellow lover of nature and gardens. This post left me weeping. Thank you.

P.s. my internal garden witch instantly questioned if the seeds are true because of the other squash you grew (nearby?). I don’t know the details and don’t want to assume you don’t know…. but just to think about it. So beautiful.

Thanks for reading. I’m so glad you enjoyed it!

No idea if the seeds are true or not, but I’m happy to wait until next year to find out!

I was led to this journal via Facebook, where I have only just now learned of Barry’s passing. Thank you for your eloquent words, and the insight you provide into this spirited man’s universe. Barry was kind to me during my Takilma years! And his son is accounted as a friend. I wiss miss him terribly.

As do all who knew and loved him. Thanks for reading!

Miles, I continue to be so grateful for the lessons learned and the beautiful lifestyle I witnessed when I visited you at Barry and Meadow’s farm. Thank you for these reflections shared, and for the beautiful images of your time with him then…and how he continues to be a presence in your garden and your home.

We were both inestimably lucky to have known Barry, and continue to be so. Thanks for reading!

I just found this lovely tribute to Barry. I knew him in the 90’s when I lived in Williams and worked in the woods as a botanist. I was in L.A. when I heard he was dying, and I wrote this song, thinking of him and the mountains, and the fires that run through our lives and our forests. I don’t know how the :homepage’ link works, so I will try to post it here as well: https://soundcloud.com/dharmika/fire-in-our-eyes

Hi Dharmika,

Thanks very much for leaving this comment and sharing that song. It’s really a beautiful piece of poetry and music. I visited Cave Junction often growing up, so the river and the land left their mark on me as well. Barry is and always will be part of that mark, inseparable from the soil and water and the life that came from them. Be well and thanks again for reaching out!

I knew Barry growing up in Takilma. This was so precious to read ♥️

Thank you for writing this tribute to Barry. I moved to Cave Junction in August 2012, and I lived in Barry and Meadow’s pod during the spring and summer of 2014. I resonate with so much of what you wrote here about your time with them.

I can’t believe I came across your heartfelt homage to Barry. I did not know he had passed, which is not surprising as I had not seen him since the late 70s when we both worked in the antinuclear movement in Florida. He was a dear friend then, and it warms my heart to get a brief glimpse into the life that unfolded after we lost contact. Thank you!

I’m so glad that you found this piece and that it had a positive impact on you, Candas! Thanks for reading and leaving this comment. 🙂

Wow, like Candas… 2023 and this piece continues to touch people. Just found it. I knew Barry in a different way, from rafting – kayaking in his case. I love how you talked about how we are often not aware we are changing and how much of an impact someone is having on us until we have changed and can look back on that change. Barry planted seeds in you. We plant seeds in each other usually without either person knowing – the planter or the planted. And the squash you grew of his was such a beautiful symbol. Thank you for writing something that is timeless and has relevancy beyond the immediate subjects.

Thanks Jennie! I’m so grateful that you found this piece and left this appreciative comment. Many people that Barry touched during his lifetime continue to enjoy the harvest of the seeds he planted in us!