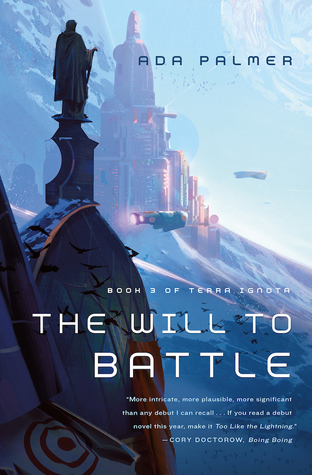

Review: Ada Palmer’s “The Will to Battle”

by Miles Raymer

The Will to Battle, the penultimate installment of Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota Quartet, is somewhat stranger than its predecessors but every bit as brilliant and entertaining. It’s an in-between tale––a bridge from one place to another. Such stories always run the risk of being needlessly convoluted or just tiresome, but Palmer manages to keep the pacing and tension high, even if the plot doesn’t move forward as much as expected.

The book’s title is pulled from a passage in Thomas Hobbes‘s Leviathan, and refers to “that tract of time wherein the Will to Battle is so manifest that humankind can no longer trust itself to keep the peace” (135). In this incipient state of war which has yet to become overwhelmingly violent, optimistic individuals may still try to prevent conflict or minimize its eventual brutality. Full-blown war, however, is considered inevitable by all soon-to-be-combatants, who utilize this solemn period for strategic lucubrations, build-up of arms, alliance-making, and betrayals.

All of this and more awaits those who summon The Will to Battle to their reading table. It’s hard to talk specifics without revealing major spoilers, so I’ll comment on my continuing love affair with Palmer’s themes and be on my way. I’m not sure why it was this book in particular that made me realize this, but Terra Ignota is probably the most sophisticated fictional interrogation of consequentialist ethics I’ve ever encountered. In the first book, one of the main characters drops this show-stopping line: “I apologize for this mismatch in the radii of our consequentialisms” (Too Like the Lightning, 197). I should have known then that this was more than pretty language, that Palmer planned to push the implications of modern consequentialism to their very limits and beyond. This became clearer as the central conflict of the first two books took shape. Then, in The Will to Battle, the term “terra ignota” was unveiled as a legal concept, and began to exert a direct and powerful force on the direction of the series. “Here at the law’s wild borders,” Palmer purrs, “there be dragons” (26). It’s impossible to know exactly where Palmer is taking us, but at this point it seems guaranteed that it’s somewhere we should want to go.

This brings up something I heard Palmer say in this wonderful interview, which is worth quoting here:

As Ursula Le Guin said in her National Book Award Speech, genre fiction writers of science fiction, fantasy, and alternate history are realists of a larger reality in which we are exploring not just the Earth that we’re in but other ways societies and worlds could be set up, expanding the breadth of imagination of our civilization and expanding the number of civilizations with which we have made a kind of first contact. Since the development of science fiction as a genre, when new technological changes have affected the world, we have had dozens of different well thought through answers to what might this do before it happens…Science Fiction fights our ethical battles before we have to do them, and is one of the things that makes humanity now more humane and ethically prepared for the speed of change we face than we have ever been before. (2:17:00)

I agree with the interviewer that this is hands down the best definition of science fiction I’ve ever heard, and I marvel that its source is a relatively young historian, rather than a seasoned scifi writer, scientist, technologist, or futurist. To return to consequentialism, I can see now that Palmer has been working with a unique concoction of considerations while writing Terra Ignota: a captivating story, exceptional world-building, amazingly complex and nuanced characters, rational optimism, unmatched familiarity with humanity’s past and possible futures, and––perhaps most importantly––an understanding that cultural narratives imbued with sufficient scope, ambition, and intelligence can have a massive impact on how we think about and actively shape the future of our species. I wouldn’t argue that no other living writer is playing this game at the same level, but I’d raise a deeply skeptical eyebrow at anyone who claimed to be doing it better than Ada Palmer. She writes not with arrogant certitude that her work will change the world for the better, but with effervescent hope that it just might.

Having already traveled through two challenging novels to reach the brink of war, readers could be understandably frustrated by a third that continues to kick the can down the road. But for my part, I continue to find everything about Terra Ignota sparkling with genius. I should also probably mention that the final chapter of The Will to Battle left me weeping––twice. I’m glad Palmer has planned a definite end to the series, which should prevent her from running out of steam, but I’m also crestfallen that I will one day have to bid these books adieu. But not yet, thank Utopia! Until Perhaps the Stars comes out next year, I’ll be rapturously waiting.

Rating: 10/10