Review: Dave Eggers’s “Zeitoun”

by Miles Raymer

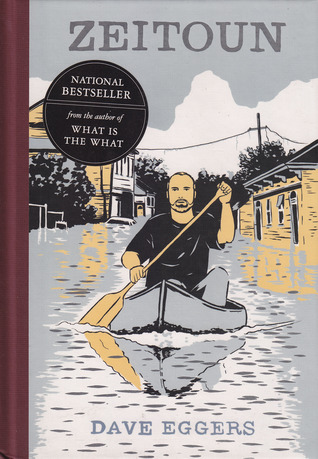

From the works of John Steinbeck to David Simon and George Packer, narrative nonfiction has played a significant role in shaping my ideas about America. Now I can add Dave Eggers to that list. I’d never heard of Zeitoun until a friend recommended it, but her description of a man undertaking a quixotic canoe journey in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina was too intriguing to ignore.

Zeitoun is the true story of Abdulrahman and Kathy Zeitoun, a Muslim-American couple living in New Orleans with their four kids when Katrina strikes. Zeitoun is a prosperous and hardworking Syrian immigrant who settled in New Orleans and built a contracting business from scratch. Kathy––a former Christian who converted to Islam as a young adult––helps Zeitoun run the business and care for the children. In many ways, the Zeitoun family is the embodiment of the American Dream.

As Katrina looms, Kathy and the kids evacuate, but Zeitoun vows to stay in the city to care for the family home and his many rental properties throughout the city. When the city floods, Zeitoun takes to the watery streets in an old canoe:

There was the canoe. He saw it, floating above the yard, tethered to the house. Amid the devastation of the city, standing on the roof of his drowned home, Zeitoun felt something like inspiration. He imagined floating, alone, through the streets of his city. In a way, this was a new world, uncharted. He could be an explorer. He could see things first. (94-5)

Zeitoun finds new purpose and a queer sense of serenity as he paddles around the city, assisting stranded residents and animals along the way. Before long, however, he is arrested and wrongfully accused of looting; his woes are compounded when his captors suspect him of terrorist activity after learning of his Syrian heritage. Denied even a single phone call, Zeitoun is held in a makeshift prison for nearly a month before he is able to contact Kathy, who has been traumatized by his disappearance. After a predictably byzantine slog through several bureaucratic bodies, Kathy is finally able to get Zeitoun released from his brutal confinement. Though they are happily reunited, Zeitoun’s feelings about America have changed:

The country he had left thirty years ago had been a realistic place. There were political realities there, then and now, that precluded blind faith, that discouraged one from thinking that everything, always, would work out fairly and equitably. But he had come to believe such things in the United States. Things had worked out. Difficulties had been overcome. He had worked hard and achieved success. The machinery of government functioned. Even if in New Orleans this machinery was sometimes slow, or poorly engineered, generally it functioned.

But now nothing worked. Or rather, every piece of machinery––the police, the military, the prisons––that was meant to protect people like him was devouring anyone who got close. He had long believed that the police acted in the best interests of the citizens they served. That the military was accountable, reasonable, and was kept in check by concentric circles of regulations, laws, common sense, common decency.

But now those hopes could be put to rest.

This country was not unique. This country was fallible. Mistakes were being made. He was a mistake. In the grand scheme of the country’s blind, grasping fight against threats seen and unseen, there would be mistakes made. Innocents would be suspected. Innocents would be imprisoned. (262-3)

This book left me wondering why the story of the Zeitoun family doesn’t have a more celebrated presence in our national memory of Hurricane Katrina. But then I stopped wondering when a quick Google search revealed this and this. Sad, sad stuff. Sad enough to make people want to forget about the whole ordeal: the original disaster, the unjust imprisonment, Zeitoun’s lionization in the wake of Eggers’s book, and the subsequent disintegration of Zeitoun’s marriage.

There seems little value in speculating about whether the Zeitoun family’s problems were already present before Katrina or were instead a result of the PTSD that both adults suffered. The only thing that’s clear to me is that reality has sullied Eggers’s final message:

A dark time has passed over this land, but now there is something like light. Progress is being made. We have removed the rot, we are strengthening the foundations. (325)

The particular weakness of narrative nonfiction is that it can be flatly contradicted after the ink dries. I do not doubt the sincerity of Eggers or the Zeitoun family, but I reject the notion that this book should transmit an authentic sense of hope to its readers. In this case, the damage was too great, the wounds too deep. Eggers thought he was writing about obstacles overcome, but he was only burnishing the surface of a story that refused to be salvaged.

Rating: 7/10