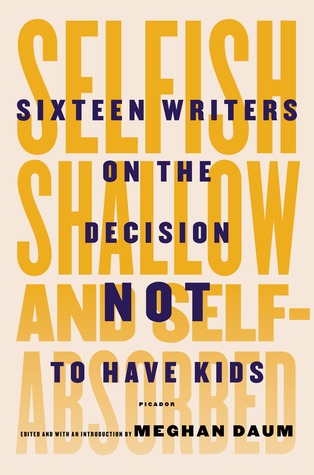

Review: Meghan Daum’s “Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed”

by Miles Raymer

I am in my late twenties, engaged to be married, and the occupant of a household that is, in many ways, an ideal environment in which to raise children. Despite these fortunate circumstances, I am deeply ambivalent about becoming a parent. So, after my fiance read Meghan Daum’s Selfish, Shallow, and Self Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, I considered it a personal necessity––and a civic duty––to read it myself.

I’m glad I did. Daum has put together an excellent collection of essays. Without exception, these offerings are well-written, carefully considered, and entertaining. I can’t say they helped me decide definitively whether I want to be a parent, but they did emphatically drive home the message that there are plenty of good reasons not to want kids. This message contravenes the dominant cultural assumption that becoming a parent is an essential and highly desirable feature of adulthood, and does so with gusto.

After internalizing this book’s various justifications for childlessness, I have two lingering worries, both of which have to do with common themes that emerge despite the authors’ eclectic backgrounds and perspectives. The first is the sneaky prevalence of “it’s all for the best” reasoning. Humans are famously good at self-justification; we spend a huge amount of time and energy weaving narratives that supposedly explain why our past choices have paid off so thoroughly. This phenomenon even applies when such assessments are flatly contradicted by objective facts. (For a crash course in the mechanisms that enable such mental gymnastics, I recommend Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me).)

Predictably, the authors in Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed spend a lot of time explaining why they chose their unconventional lifestyles. The stories make sense, and the reasons seem justifiable, but I found it problematic that some of the authors felt comfortable making assertions about what kinds of parents they’d have been, or about precisely how parenthood would have changed their lives. Take this example from Paul Lisicky’s essay, in which he addresses his “Child-Who-Might-Never-Be”:

It is too late for me to be the kind of parent you might want. I will not be like the parents of your friends. I will probably hang out with your friends, and when they come to the house to visit, you’ll probably want to see me as much as they want to see you. My mother was just like that, remember? We will squeeze chocolate syrup onto our yogurt. We will take the stereo out into the backyard and turn up the volume too loud…We will name the birds in the branches and on the lawn…I will probably embarrass you by the way I dress…You will get used to my awkwardness, my kisses, my dropped keys, my trying to be present with you, now and now and now and now. (75)

This is a touching piece of prose, written with sincerity and artfulness. I find it bizarre, however, that Lisicky feels able to confidently depict the kind of parent he would be, to a child who will never exist. It seems that, as with any life-altering event, Lisicky would change in myriad unexpected ways were he to become a parent; to speculate about his strengths and weaknesses in that role is shooting in the dark. Moreover, such speculations are poor explanations for why one shouldn’t be a parent in the first place. While the writers in this book present plenty of legitimate arguments for why they don’t want to be (or shouldn’t be) parents, I was annoyed when those cases were built on unverifiable assumptions about exactly how parenthood would have affected them.

Another problem is that, despite the authenticity of these personal accounts, almost all of them implicitly accept the choice between parenthood and career as an unambiguous binary, with writing as a substitute for parenthood. Editor Meghan Daum acknowledges this problem in the introduction:

Artists––especially writers––need more alone time than regular people. They crave solitude whereas many people fear it. They resign themselves to financial uncertainty whereas most people do anything they can to avoid it. Moreover, if an artist is lucky, her work becomes her legacy, thus theoretically lessening the burden of producing a child to carry it out. (6)

There certainly isn’t a problem with writers who cultivate a linguistic legacy rather than a genetic one, but most of these essays make the reader feel like it would be illegitimate to not want children in the absence of such ambitions. I would have preferred they go a step further, pointing out the insidious cultural myth that one needs to leave any legacy at all, and should slavishly devote his- or herself to it. So while these writers are open-minded in their calculus about child-bearing, most of them come off as buying into the dogged careerism that wrecks the sanity of many Americans. One’s identity needn’t be built upon the foundation of parenthood, but it also needn’t be tied to a particular activity or job.

One of the writers, Geoff Dyer, shares my view:

If you can’t handle the emptiness of life, fine: have kids, fill the void. But some of us are quite happy in the void, thank you, and have no desire to have it filled. Let’s be clear on this score. I’m not claiming that I don’t need to have kids because my so-called work is fulfilling and gives my life meaning. To be honest, I’m slightly suspicious of the idea of an anthology of writers writing about not having kids…If this is a club whose members feel they have had to sacrifice the joys of family life for the higher vocation and fulfillment of writing, then I don’t want to be a part of it. Any exultation of the writing life is as abhorrent to me as the exultation of family life. (201-2, emphasis his)

Hear, hear.

Of the many personal proclamations on offer here, my favorite was Jeanne Safer’s commendable rejection of the notion that life can happen without regrets:

There is nobody alive who is not lacking anything––no mother, no nonmother, no man. The perfect life does not and never will exist, and to assert otherwise perpetuates a pernicious fantasy: that it’s possible to live without regrets. There is no life without regrets. Every important choice has its benefits and its deficits, whether or not people admit it or even recognize the fact: no mother has the radical, lifelong freedom that is essential for my happiness. I will never know the intimacy with, or have the impact on, a child that a mother has. Losses, including the loss of future possibilities, are inevitable in life; nobody has it all. (195)

Although Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed hasn’t resolved my ongoing inquiry about whether to have children, it has given me plenty to ponder. It is important to admit that, no matter what my partner and I choose, we will always feel there was something missing, some stream bed of precious stones left unturned. We can also rest assured that, a few decades on, we’ll find ourselves dutifully constructing tales that justify our choice as, in hindsight, the best possible option.

Rating: 7/10

I really enjoyed this review, and plan to read this book! It’s an interesting thing to witness how people justify such big life decisions, and if I was going to push back on one of your critiques it would be to say that this seems to be something that childless people care constantly pressured to do. So the narratives and assertions you find troubling are likely the result of years of criticism and skepticism about this choice.

I love that final quote–what a great statement of truth on this issue and life in general!

Thanks for your review!

Thanks for reading Katie! Your pushback is duly noted, and when you read the book, you’ll see that most of the authors take up in detail the issue of being pressured to justify their decisions. My critique wasn’t that these kinds of justifications are problematic per se, but that it doesn’t seem prudent to exude certainty about what kind of parent a childless person might have been, or about how parenting would change that person’s life, because they (and we) simply don’t know.

But perhaps that’s a distinction without a difference. What do you think?