Review: Peter Turchin’s “Ages of Discord”

by Miles Raymer

The work of Peter Turchin has been my most exciting intellectual discovery of 2019. After my mind was blown by War and Peace and War earlier this year, I was delighted to learn that Turchin has published a more recent book demonstrating how the principles of cliodynamics have played out in America. Ages of Discord is a cutting critique of American history that approaches well-known problems from unexpected angles; it’s a must-read for history buffs and anyone interested in comprehending the precarious, scary trends that dominate 21st-century America.

This review comes with a couple caveats: First, the arguments in Ages of Discord depend heavily on mathematical models that I find difficult to grasp and definitely can’t assess for validity. Although Turchin does a fine job of making his approach accessible to readers unversed in his mathematical background, there is still a lot that went over my head. So I just need to acknowledge upfront that, aside from the normal hiccups one expects from quantitative models of the real world, I’m assuming there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with Turchin’s findings. More than anything, my confidence derives from Turchin’s regular and responsible attempts to highlight the limitations of his mathematical models, even as he advances them with deftness and deserved aplomb.

The second caveat is that the experience of reading Ages of Discord is somewhat difficult to articulate because it’s so visual. In a book shorter than 250 pages, five of them are devoted solely to listing all of the tables and figures contained in the text. I will reproduce a handful of the most important figures to round out this review, but readers should keep in mind that it’s just a tiny taste of Turchin’s whopping data-punch.

Contrary to the norm in today’s nonfiction, this book’s subtitle––“A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History”––actually denotes why the author’s method is important and special. “What is Structural-Demographic Theory (SDT),” you ask? The short answer is that it’s our best current tool for applying quantitative analysis to historical information. Given its new-kid-on-the-block status (it was only invented thirty years ago), readers should engage with this theory from a place of healthy skepticism, looking for weaknesses but remaining open to the possibility that Turchin’s on to something.

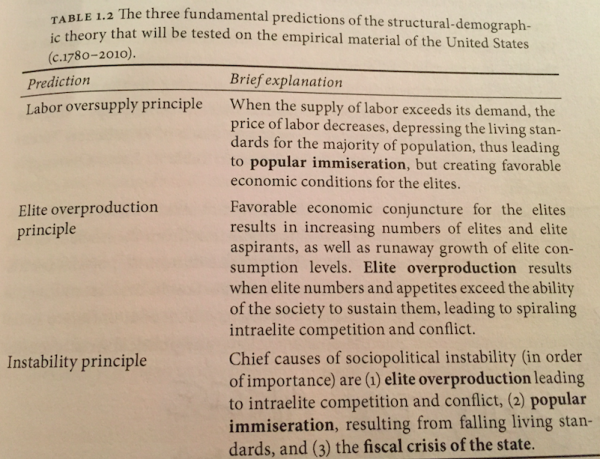

SDT seeks to understand and predict historical trends by examining the dynamics between three basic principles: the Labor Oversupply principle, the Elite Overproduction principle, and the Instability Principle. Turchin’s definitions here:

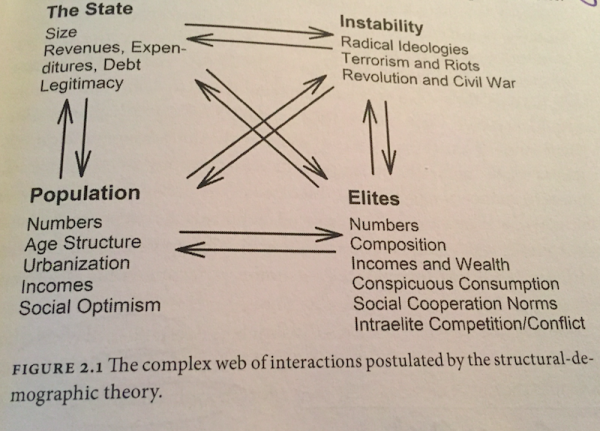

Taken together, these principles represent how the general population, the elite population, the state, and political instability interact and change over time. Here’s a visualization of this complex web of relationships:

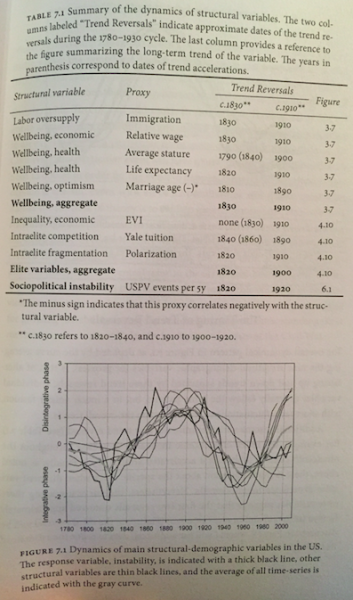

The condition of each principle over a defined period of time can be accessed via different “proxies”––aspects of sociopolitical life for which data are available. Examples of such proxies are immigration, relative wage, and average stature (Labor Oversupply); economic inequality, college tuition, and cost of elections (Elite Overproduction); and homicide, deaths in riots, and public trust in government (Instability). Using these proxies and others, Turchin creates an amazing series of composite graphs that show clear trends. Here is one of them:

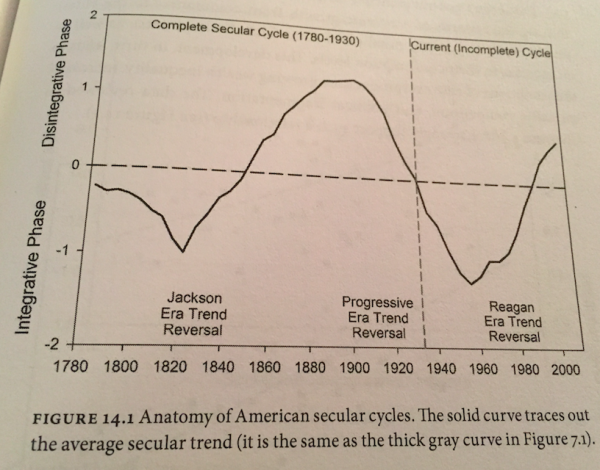

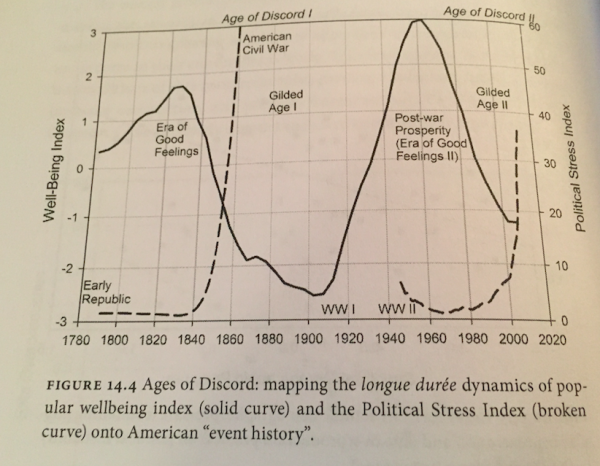

These trends reveal the distinct integrative phases––generally positive eras with low inequality, high social mobility, and strong stability/cooperation––and disintegrative phases––generally negative eras with high inequality, low social mobility, and weak stability/cooperation––of America’s secular cycles. One complete integrative phase plus one complete disintegrative phase equals one complete secular cycle. The above example shows the entirety of America’s first secular cycle (1780–1930), as well as our current, unfinished secular cycle (1930–today). Here are two additional graphs that tell a similar story:

The essential findings are that the first secular cycle began with an integrative phase (the Era of Good Feelings), and then entered a disintegrative phase during the 1830s (Jackson Era). After bottoming out during the Civil War and the Gilded Age that followed, America entered another integrative phase during the early 20th century (Progressive Era). This integrative phase lasted through the Depression, World War II, and the postwar era (Era of Good Feelings II), and then reversed into our current, unfinished disintegrative cycle in the 1970s and 80s (Reagan Era followed by a second Gilded Age).

As you can see, we are currently living through America’s second disintegrative phase, or “Age of Discord.” Although Turchin’s method of getting there is novel, this will not be news to anyone alive in America today, nor to the billions of non-Americans watching on the sidelines as we flounder. Perhaps to avoid seeming overly deterministic or cynical, Turchin is cautiously optimistic about what the immediate future has in store:

We are rapidly approaching a historical cusp at which American society will be particularly vulnerable to violent upheaval. However, a disaster similar to the magnitude of the American Civil War is not foreordained. On the contrary, we may be the first society that is capable of perceiving, if dimly, the deep structural forces pushing us to the brink. This means we are uniquely equipped to take policy measures that will prevent our falling over it. (242)

Given the remarkable intelligence Turchin displays, it is frustrating that he doesn’t offer an opinion regarding which “policy measures” would give us the best chance to reach our next integrative phase with as little suffering as possible. “I hope that the theory and data explained in this book will contribute to finding solutions that will help us find a non-violent escape from the crisis,” he writes, but his unwillingness to advocate for particular policies makes Ages of Discord feel incomplete––less invigorating and more academic than its urgent message ought to be (248).

Conspicuously, Turchin also doesn’t comment on the ways in which new global pressures such as climate change, technological advancement, and bioengineering might accelerate, retard, or disrupt our current secular cycle or those that may follow. Even so, Ages of Discord is one of the better American history books available. Readers will have to draw their own conclusions about what Turchin’s work demands of citizens eager to save America from itself.

Rating: 9/10