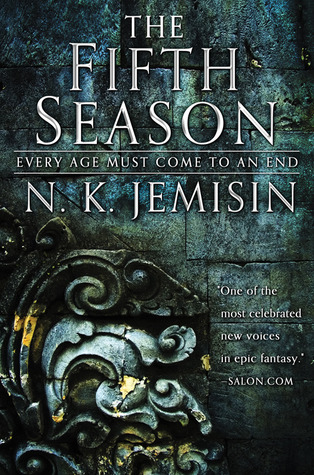

SNQ: N.K. Jemisin’s “The Fifth Season”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season is the first installment of The Broken Earth, a fantasy trilogy set on a vast continent called the Stillness, “which is not still even on a good day” (7). The inhabitants of the Stillness experience frequent seismic events and other natural disasters, including brutal “Fifth Seasons”––long winters lasting six months or more that occur roughly every few hundred years. To survive in this hostile environment, humans living in the Stillness have created strict cultural traditions, including a caste system and “stonelore,” mythological rules and guidelines for how to survive Fifth Seasons. Dominating the Stillness is the Sanze Nation, which has survived seven Fifth Seasons to become the continent’s most powerful socioeconomic force. In its capital city of Yumenes, a military organization called “The Fulcrum” trains “orogenes,” people who have “the ability to manipulate thermal, kinetic, and related forms of energy to address seismic events” (462). Imperial Orogenes are extremely powerful, but their activities and use of orogeny are tightly controlled by a vicious order called Guardians. There are also massive floating obelisks that pepper the Stillness’s skies––mysterious objects presumed to be remnants of some ancient and forgotten civilization––and a humanoid race of “stone eaters” about whom little is understood. Against the backdrop of the Stillness’s fraught history and environmental vicissitudes, Jemisin introduces three protagonists in different stages of life: a girl named Damaya, a young woman named Syenite, and a middle-aged mother named Essun. All three characters are orogenes, and their stories are connected in clever and surprising ways.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- As a reader who typically prefers science fiction over fantasy, I found this book impressive. The worldbuilding is especially good, with Jemisin commanding a strong sense of place, history, and cultural depth throughout the book. Her vision of a civilization built on environmental adaptation and principles of magical geology is truly unique, including an assortment of Stillness-specific terms that are helpfully defined in an appendix at the back of the book. For all its made-up-ness, this feels like a real world.

- Jemisin’s characterization is also top-notch. I immediately felt an affinity for all three protagonists, remained fully engaged with their story arcs, and was always excited to learn what the next chapter had in store. Mastery of orogeny seems to be determined by one’s capacity to balance intense emotion with self-control, and this dynamic pushes the character development along nicely.

- Jemisin’s prose is decent, with some good humor thrown in from time to time. Where the writing stands out is in her use of second person perspective, which is deployed effectively in one of the three story strands. This is pretty uncommon and gives the book a fresh feel.

- Thematically, Jemisin is concerned with issues of social and climate justice, primarily overcoming systems of oppression and living in harmony with nature. These worthwhile themes have the potential to get histrionic, but are handled quite well in this first book. I am somewhat concerned that the trilogy will fall into a classic revolutionary narrative, as hinted by one of the main characters: “You can’t make anything better…The world is what it is. Unless you destroy it and start all over again, there’s no changing it” (371). This is the kind of message I used to embrace in the heat of my youth, but now see as oversimplified and anti-progressive. These days, my progressivism is much more incrementalist with a strong preference for nuanced rejections good/evil binaries. I’m curious to see which path Jemisin takes here.

- A related concern is that Jemisin might be working with a kind of halcyon days mentality that laments modernity and seeks to recover an imagined utopia before “people began to do horrible things to Father Earth” (379). This is another perspective I used to buy into but have since walked away from––essentially a liberal version of “Make America Great Again.”

- Finally, there are a ton of open questions and unexplained phenomena in this book, so I’m really hoping that most or all of these loops get closed in the next two books. I’m really excited to continue the series.

Favorite Quotes:

The earth does not like to be restrained. Redirection, not cessation, is the orogene’s goal. (117)

As those first weeks pass into months and she grows familiar with the routine, she begins to understand what it is that the older orogenes display: control. They have mastered their power. No ringed orogene would ice the courtyard just because some boy shoved her. None of these sleek, black-clad professionals would bat so much as an eyelash at either a strong earthshake, or a family’s rejection. They know what they are, and they have accepted all that means, and they fear nothing. (196)

According to legend, Father Earth did not originally hate life.

In fact, as the lorists tell it, once upon a time Earth did everything he could to facilitate the strange emergence of life on his surface. He crafted even, predictable seasons; kept changes of wind and wave and temperature slow enough that every living being could adapt, evolve; summoned waters that purified themselves, skies that always cleared after a storm. He did not create life––that was happenstance––but he was pleased and fascinated by it, and proud to nurture such strange wild beauty upon his surface.

Then people began to do horrible things to Father Earth. They poisoned waters beyond even his ability to cleanse, and killed much of the other life that lived on his surface. They drilled through the crust of his skin, past the blood of his mantle, to get at the sweet marrow of his bones. And at the height of human hubris and might, it was the orogenes who did something that even Earth could not forgive: They destroyed his only child. (379-80)