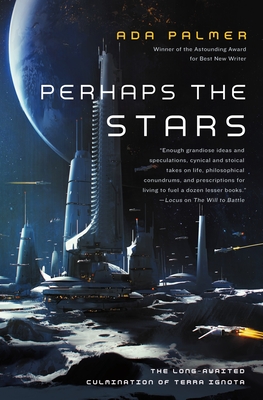

Review: Ada Palmer’s “Perhaps the Stars”

by Miles Raymer

There are times when I feel utterly incapable of expressing my appreciation and admiration for a particular book. This is the case with Perhaps the Stars, Ada Palmer’s magnificent conclusion to her Terra Ignota Quartet. Please know, dear reader, that even if you read this entire review, and my reviews of the other three Terra Ignota books (Book 1, Book 2, Book 3), I will never have enough words––or the right words––to tell you how deeply grateful I am to be alive in a time when such stories are conceived and disseminated. Palmer’s literary achievement is so brilliant and powerful that it defies this humble reviewer’s ability to heap sufficient praise; I will try to tell you how great these books are, and I will fail.

In my senior thesis for my undergraduate degree, I posited a theory of “ethically complex narratives,” which I described as narratives that “struggle against the tendency to categorize moral agents and their actions within traditional dichotomous ethical formulas, such as ‘good and evil,’ ‘right and wrong,’ or ‘strength and weakness.'” I’ve come across many great stories that meet the criteria for ethical complexity, but none more effectively than Terra Ignota. Palmer’s 25th-century future is, above all else, a vision of courageous optimism in which even the ostensible villains generally strive to uphold the core tenets of humanism and basic decency. Perhaps the Stars describes a World War in which nearly all combatants are honorable and laudable, depending on your personal and ideological inclinations. It is notoriously difficult to generate genuine tension in such scenarios, and this is why most writers succumb to ethical simplicity, usually in the form of an overbearing antagonist who wants to control everything or destroy the world because…well, because we need that in order to generate conflict, and also to dispel any ambiguity regarding who we are “supposed” to root for. Ada Palmer is the living antithesis of that lazy approach.

It’s nearly impossible to find an author with a broader range of influences. Palmer’s prose is replete with intelligent observations about languages, historical periods, philosophical traditions, technological possibilities, political structures, and mythological traditions. One fascinating feature of Perhaps the Stars is that it’s a retelling of Homer’s The Iliad, or perhaps a “remix” might be a more accurate term. It also contains a single chapter that’s a rollicking reimagining of The Odyssey. I prepared for this by reading Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of The Iliad and a few secondary texts, and that work really paid off. While I’d have to be as smart as Palmer to fully grok all of her allusions, many of them clicked for me after immersing myself in Greek Mythology for a few months. I had a huge amount of fun witnessing Palmer unfurl each new connection between her story and Homer’s.

Palmer is unflinching in her love of humans, who she refers to as “the instruments that carve the path from cave walls to the stars…[and who] built this world and will build better ones” (2). She is also appropriately caustic when it comes to pointing out the many failings of “we who build so much and burn it, bumbling humanity” (540). She is nothing if not an epic thinker, and the plot of Perhaps the Stars hinges on nothing less than the longterm future of our species. Without dropping spoilers, I will say that in this book the core conflict of the War is revealed to be something quite different from what was previously indicated––a satisfying reveal that elevates the narrative to richer philosophical territory than it has previously visited. She also provides thoughtful and moving commentary on the nature of human relationships, the dangers and benefits of tribalism, the value of loyalty and political pragmatism, the tension between comfort and exploration, and humanity’s pressing need to become kinder in its dealings with other living things.

One potential stumbling point is that Palmer refuses to give direct explanations for a couple of her major conceits. This is sure to disappoint some readers, and I will admit to being a little irked about it at first. But the more I think about it, the less frustrated I become. This could be because I seek to anchor an unalloyed adoration of these books in my memory, or because in the end Palmer’s tale could not have been told in a way that perfectly satisfies my preferences for narrative coherence. Whatever the case, sometimes we choose to simply love something without criticism or caveat. In the final analysis, I realize that Terra Ignota drew that choice from me as easily as I draw breath.

I’d like to wrap up with my favorite quote from this 2020 interview with Palmer:

As Ursula Le Guin said in her National Book Award Speech, genre fiction writers of science fiction, fantasy, and alternate history are realists of a larger reality in which we are exploring not just the Earth that we’re in but other ways societies and worlds could be set up, expanding the breadth of imagination of our civilization and expanding the number of civilizations with which we have made a kind of first contact. Since the development of science fiction as a genre, when new technological changes have affected the world, we have had dozens of different well thought through answers to what might this do before it happens…Science fiction fights our ethical battles before we have to do them, and is one of the things that makes humanity now more humane and ethically prepared for the speed of change we face than we have ever been before. (2:17:00)

This remains (and I imagine will remain) the best definition of science fiction I’ve ever heard; it’s also a perfect description of Palmer’s work. Like all great science fiction, Palmer’s story is as much about the present as it is about what may come to pass. Today, humanity is on the brink of achieving civilizational escape velocity that could propel us into an infinitely bright future, but our lesser angels––our bellicose bickering and atavistic urges––may yet wreck it all. I can’t begin to enumerate the diversity and depth of the ethical battles these books fight on behalf of a better future for humanity and life more generally. Most authors would be lucky to exhibit commensurate creativity and insight in an entire career, let alone a single series. Terra Ignota not only secures Palmer’s place in the highest echelon of science fiction authors, but earns her a position as one of our finest living writers in any genre. I can’t wait to see what she comes up with next.

Rating: 10/10