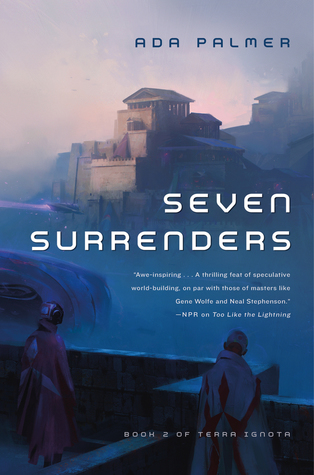

Review: Ada Palmer’s “Seven Surrenders”

by Miles Raymer

Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota Quartet continues to delight and astound me. Since Seven Surrenders was originally planned as the second half of Too Like the Lightning, please start with my review of that book; I won’t repeat key information about the series that was covered there. Better yet, just stop reading this review and get your hands on a copy of Too Like the Lightning––you won’t regret it.

Seven Surrenders picks up where the previous book left off, bringing the first part of Palmer’s story to an incredible and surprising climax. The main preoccupation here is with the root causes of war, and the question of whether war is an ineradicable aspect of human nature and society, or whether we can permanently outgrow it. While reading, I found myself often reminded of the following quotes:

As in the mechanism of a clock, so also in the mechanism of military action, the movement once given is just as irrepressible until the final results, and just as indifferently motionless are the parts of the mechanism not yet involved in the action even a moment before movement is transmitted to them. Wheels whizz on their axles, cogs catch, fast-spinning pulleys whirr, yet the neighboring wheel is as calm and immobile as though it was ready to stand for a hundred years in that immobility; but a moment comes––the lever catches, and, obedient to its movement, the wheel creeks, turning, and merged into one movement with the whole, the result and purpose of which are incomprehensible to us. (War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy, 257-8)

History does not prove the inevitability of war, but it does prove that customs and institutions which organize native powers into certain patterns in politics and economics will also generate the war-pattern. The problem of war is difficult because it is serious. It is none other than the wider problem of the effective moralizing or humanizing of native impulses in times of peace. (Human Nature and Conduct, by John Dewey, 115).

Seeking a metaphor that could honor causal complexity, Tolstoy likened the tensions and breaking points of war to a kind of mysterious clockwork. For his part, Dewey saw war as the result of our inability to wisely channel our bellicose tendencies through sociopolitical structures that would solve problems without the need for armed conflict. Over the last century, the clockwork has remained mysterious but not entirely inscrutable, and our institutions have proven capable of preventing some wars, but not all.

Time will tell if Ada Palmer deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as writers like John Dewey and Leo Tolstoy, but I’m pulling for her. In Seven Surrenders, the plot, characters, and mid-25th-century setting of Terra Ignota all become more intricate and fascinating. Executed with superior depth and nuance, Palmer’s political intrigue boggles the mind as she invites readers to ponder strange and terrifying questions such as:

- What kind of war should a species expect after several centuries of peaceful technological progress, with no one left alive who has ever fought one?

- Does an increased length of time between major wars cause a corresponding increase in the potential devastation when a new war finally breaks out? And if so, should we fight wars regularly to soften the blow of future wars?

- Is it better for individuals to constantly fight one another if doing so makes it impossible to organize en masse confrontations?

- Do we need war and suffering to create people capable of enduring and to keep progress moving forward?

- Do we need heroes in order to give war a human face?

- Should we accept a global autocracy if doing so seems the surest path to peace and prosperity?

- Is it sufficient to live for happiness alone, or will humanity always crave something more?

Although delivered perfectly in the context of the story, two dueling passages read to me as words one might pose to humanity in its present state:

Change is the enemy here, too many changes, too big, too fast…The best thing we can all do over the next days is take it slow…We are all shocked by what’s happened…and our instinct is to want shocking solutions, to destroy the system that’s gone so wrong, to purge the guilty, and make something new. We mustn’t be so rash…If I had a time machine I could go back in time and find a king, any ancient king who ever lived, and bring them here and they would weep with envy for what the most modest of us has…This world is not perfect. It’s scarred by mistakes, past and present, but this is the utopia past generations worked to make for their descendants, not a perfect world, but the best one humanity has ever had, by far…Calm, slow change is what we need, to make this good thing better, not war, not revolution, not tearing it all down. If we all dedicate ourselves to saving this good world, and to improving this good world, we can preserve the good, and make the bad parts better. (286-8)

An hour ago…the Anonymous spoke publicly for the first time in history. They urged us all to move slowly, to keep our reactions to this crisis in check in order to preserve what they have called utopia. I disagree…I don’t believe that, having recognized our long-term dependence on these corrupted systems, we should try to keep ourselves dependent on them…Better to act honestly and quickly than to succumb to corruption and base means to prop up what is already broken. (296)

Both of these statements are true, of course, and both should stir everyone to action. As I’ve come to expect, Palmer’s command of ethical complexity is impeccable. By novel’s end, the world is on the precipice of a new and utterly unpredictable war, plunging headlong into terra ignota (Latin for “unknown land”):

If you are my contemporary, reader, brought to this history to understand the days of transformation you are still living through, be patient, pray. Do not act rashly, spurred by your revulsion at the dark underbellies I have exposed here…So many on all sides of this are bloodstained, perverted, mad, but also noble, wise, untiring servants of your interests, who will give their days, their years, their deaths, to guard this world for you, or make a better one. I do not ask you to forgive them all, just to have reasons beyond rash grudges or affections when you choose to fight and kill for one side, or the other. (362-3)

The Will to Battle awaits!

Rating: 10/10