SNQ: Sarah Jaquette Ray’s “A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

Sarah Jaquette Ray’s A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety isn’t a book about how to solve the climate crisis. Rather, it’s about how to cultivate a mature, compassionate, and resilient mindset that will allow climate activists to pursue climate justice in a healthy and sustainable fashion. Ray presents a series of lessons about the psychological challenges that climate pressures pose, especially for young people who have trouble imagining positive visions for their futures. She also offers conceptual and practical tools readers can use to set realistic goals, overcome negativity bias in our own minds and the media, commit to self-care, avoid burnout, cooperate across partisan divides, and embrace narratives of personal and natural abundance.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- As a fellow resident of Humboldt County, California, it was a pleasure to read Professor Ray’s book. I’m really proud that someone in my community produced this piece of research.

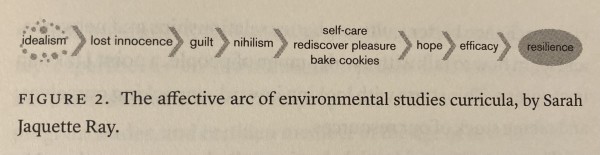

- Ray’s main argument is that our efforts to educate students and citizens about climate change must be guided by emotional intelligence in order to effectively communicate the urgency of the situation without triggering apathy or despair. She demonstrates commendable humility by stating that she used to teach environmental studies in a way that was emotionally destructive for some of her students and herself; to correct this problem and take a more positive approach, Ray created the “affective arc of environmental studies”:

- Ray does an excellent job of articulating how demoralizing and discouraging it is to live under the shadow of an apocalyptic climate narrative. “Doomsayers can be as much a problem for the climate movement as deniers, because they spark guilt, fear, apathy, nihilism, and ultimately inertia,” she writes. “Who wants to join that movement?” (35). Instead, Ray favors “reframing environmentalism as a movement of abundance, connection, and well-being” (7). In my view, this isn’t just the most sensible way to address our climate woes, but also the absolutely necessary approach we need to help people engage in climate work in a healthy and sustainable manner.

- Encouragingly, Ray cautions against becoming overly tribal. She says we should be open to dialog and collaboration with people who don’t agree with us about the origins or intensity of the climate problem, or who have differing ideas about how to solve it.

- I found Ray’s chapter on narrative framing especially smart and useful. Her discussion of “progressive” vs. “declension” narratives was new to me, and I agree with her that both stories are true in their own way, even if neither constitutes the whole truth. Ray urges readers to ignore oversimplified or sensationalized narratives in the media, and focus instead on consuming and telling nuanced stories that engender compassion and seek common ground.

- I had a lot of critiques of this book, a couple of which I’ll share below. But first I just want to say that my disagreements with Ray’s perspective were extremely positive and productive for me. She’s coming from a heartfelt, informed, and authentic place, and I appreciate and respect that even if I don’t agree with her about everything.

- Probably my biggest disagreement with Ray has to do with her belief that “Climate change is inextricable from social justice issues” (25)––hence her use of the term “climate justice” throughout the book. I first encountered this idea when I read Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything in 2014, and I totally bought into it. Since that time, I’ve come to believe not only that there are distinct and important differences between the climate movement and movements for social justice, but also that the climate movement should distance itself from certain aspects of social justice in order to broaden its capacity for effective coalition-building and implementation of climate-friendly policies. This is largely a reaction to rising culture war tensions in America and elsewhere that have revealed deep and profound disparities in how people conceptualize and advocate for social justice. Given that people already disagree about how best to pursue technical goals such as reducing carbon emissions, I find it baffling that activists such as Ray, Klein, and others seem to think that the situation will become more tractable if we start injecting demands to address, for example, racism, sexism, or indigenous sovereignty into that conversation. Practically speaking, I think a better approach is to cast as wide a net as possible when it comes to getting people on board with ameliorating the climate crisis (Ray’s strategies will help here!), and then use that momentum to push for relatively narrow but highly impactful policy goals, such as a carbon tax, development of carbon capture technology, renewables, cold fusion, nuclear power, or tighter regulations for industrial emissions. But time will tell, and I’ll be happy to admit my error if the climate justice model ends up being the most effectual.

- Finally, I want to air some moderate skepticism about one of Ray’s underlying assumptions, which is that solving the climate crisis depends primarily on humanity’s capacity for collective action. Again, this is an idea I used to fully accept but have drifted away from in recent years. Given the current hyper-concentration of global wealth and influence, I think it’s increasingly likely that the decision about whether to get serious about climate change will be made by a relatively small number of immensely powerful elites. Citizens of democratic societies may be able to play some small role in electing representatives or pushing for better environmental policies, but I’m well past the point where I think the choices of individual consumers can generate the scale of change we need. Additionally, when we consider new technologies such as solar geoengineering (which I have done here, here, and here), we see that just one rogue nation or even a ballsy billionaire could exert a significant impact on global temperatures for better or worse, the rest of us be damned. In light of this, Ray’s book might have benefitted from a stronger dose of “don’t worry, be happy” for us regular folks. I’m all for making climate work healthy and sustainable for those who want to go into it, but I’m also fine with telling most people to just relax and let it go if that’s not how they want to spend their time or energy. I’m increasingly dubious about messages that tell us “everyone is responsible” for taking effective climate action; even if delivered sensitively, the psychological outcome of such messages might be more harmful than helpful.

Favorite Quotes:

Reframing environmentalism as a movement of abundance, connection, and well-being may help us rethink it as a politics of desire rather than a politics of individual sacrifice and consumer denial. (7)

As a matter of survival, we need to think beyond eco-apocalypse and nurture our visions for a post-fossil fuel future. Our radical imaginations will also make visible all the good things that are being done, allow us each to see ourselves as a crucial part of a collective movement, and replace the story of a climate-changed future as a frightening battle for ever scarcer resources with one that highlights personal abundance––where there is plenty of time and energy to do the work needed to ensure that we can all be good ancestors to the many generations yet to come. (11)

People are profoundly disturbed by climate change, and being told that it is the fault of our own moral failings is not only demoralizing but factually wrong. It does not help us muster the stamina to stay involved in environmental work for the long haul. Instead, it can lead to various forms of self-erasure, or cause people to give up in despair, choosing short-term avoidance and apathy over long-term climate justice. (24-5)

Contrary to what social media articles, news outlets, friends, classes, and parents tell us, it’s not a battle between deniers and believers, or those who are wrong and those who are right. Rethinking who the “enemy” is can change our emotional orientation toward climate action. There’s no monolithic army of hostile opponents, but rather a fragmented group of stakeholders with disparate interests, understandings, and needs. (38)

Knowing that we are part of a collective gives us permission to rest. We can recover from our exertions knowing that others, who also have taken care to sustain themselves, can take over the work. We all must take care of ourselves so that we can step up when others need to tend to themselves. The perception that social change happens only on an individual scale creates defeatism. Of course we cannot solve the problems by ourselves. (70)

In general climate change is contributing to a terrible sixth extinction. But overall societal well-being is as good as it’s ever been. These two “truths” don’t cancel each other out, and of course, one could argue that the former is a result of the ladder. There are a lot of gray areas. The goal is not to paper over our feelings of fear and despair with a rosy perspective. Rather, we need to recognize that there is complexity and ambiguity in the world––good stuff and bad stuff. It can feel irrational or indulgent to turn away from the bad things that are happening. But it is possible to accept that some things are getting better while also imagining how to address the world’s intractable problems. Acknowledging the successes is necessary in order to identify where to devote our energies. (86)

Find beauty, savor the small gifts of being alive, see everything you possibly can through the lens of being blessed rather than victimized, recalibrate your efforts toward the small and local, collect and create positive stories, heed your calling by not trying to be more than you are, take yourself less seriously, and pause to inhale deeply and honor the moment. This is what it means to learn how to die in the Anthropocene. (126)