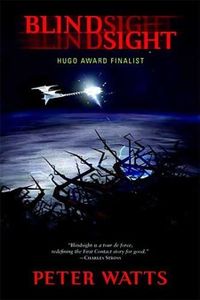

Book Review: Peter Watts’s “Blindsight”

by Miles Raymer

This is the kind of book I long to be intelligent enough to fully comprehend, although to purport having done so would be to ignore Blindsight‘s unnerving central message. Blindsight is an incredibly dark, thought-provoking tale that is equal parts science fiction, horror, and psychological thriller. Relying on a one-two punch that alternates between a heady preoccupation with the limits of human comprehension and a devilish desire to expose the flimsiness of interpersonal relationships when held up against a cosmic background, Peter Watts repeatedly robs the reader of even the most basic convictions about the value of sentience and the emotions that supposedly make life worth living. The result is an exhausting, exhilarating, and undeniably frightening novel that capitalizes on the small but infinitely exploitable spaces between our ideas of who we are and the scientific realities of what we must be.

Blindsight is narrated by Siri, a “Synthesist” (Watts’s fancy title for “transhuman sociopath made useful”) on a deep space mission to investigate an alien signal. It’s an all too familiar scifi exposition, but Watts does an admirable job of breathing new life into what is essentially the old we-meet-ET-and-get-our-minds-blown scenario. Siri’s combination of emotional detachment and technological augmentation make him suitable as an “objective observer” who isn’t supposed to do anything for the mission except watch, learn, and send summary reports back to Earth. It’s a perfect setup for a tale of violent disillusionment, and also a clever commentary on the ways that people (fictional and otherwise) feign objectivity in order to distance ourselves from the consequences of our opinions and actions.

Siri’s character arc cannot be analyzed in much detail without giving away crucial plot points, so suffice it to say that our Synthesist and his fellow star-travelers are in for one seriously horrific ride. Watts does an exceptional job of using his characters to probe difficult questions about the nature of consciousness and the issue of free will. The book becomes a blend of ghost story and morality play as Siri and company explore an alien craft that causes them to hallucinate and question their own sanity. Watts’s writing is dense and technical; he deploys a formidable surfeit of knowledge spanning myriad scientific disciplines, including but not limited to particle physics, evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and psychology. It’s easy to get lost in Blindsight, which would be off-putting if that weren’t pretty much the point of writing a book like this. Mercifully, Watts tosses an adequate supply of simplified breadcrumbs into his dialogue and description that enable less tech-savvy readers to follow major plot developments. The story is also deeply ambiguous at times, making this both a challenging and fruitfully interpretable read.

It’s worth pointing out that, judging from the content of this particular work, Watts’s views about the value of humanity and our place in the universe are almost comically cynical. A reasonable case could be made that Blindsight is the product of a highly intelligent but hopelessly nihilistic mind. Imagine Rust Cohle from True Detective on steroids. If this book has a major flaw, it’s that Watts is so enamored with his own darkness that he fails to explore anything other than the worst case scenario at almost every turn. The results would be deplorable if they weren’t so damned mind-bending and fiendishly fun.

While Blindsight’s ultra-grim aura easily could have outworn its welcome, I experienced the book as an engrossing and raucous rekindling of the ancient trickster narrative. Watts is a master of subversion, always seeking to undermine the foundational assumptions of his characters and readers. I’ve read similar authors whose work didn’t have much impact on me or just made me feel cheated, but for some reason I can’t quite articulate, Watts managed to strike a nerve (more than a few, actually).

Here is a taste of what I’m talking about:

There was a model of the world, and we didn’t look outward at all; our conscious selves saw only the simulation in our heads, an interpretation of reality, endlessly refreshed by input from the senses. What happens when those senses go dark, but the model––thrown off kilter by some trauma or tumor––fails to refresh? How long do we stare in at that obsolete rendering, recycling and massaging the same old data in a desperate, subconscious act of utterly honest denial? How long before it dawns on us that the world we see no longer reflects the world we inhabit, that we are blind? (175)

How do you say We come in peace when the very words are an act of war? (307)

Blindsight is a book that exposes the humanity’s contradictions without trying to reassure us that everything will be okay in the end. It’s a heroic and chilling attempt to view us through the perspective of a vast and indifferent universe that cares nothing for our petty disputes, emotions, aspirations or failings. It is a work of impressive (albeit lopsided) creativity that left me feeling breathless, confused, scared, and––quite unexpectedly––enlightened. I expect to be mulling it over for a long time.

Rating: 9/10

Nice! Looks like a book I might want to read.

You definitely should. Was planning to recommend it to you later today!