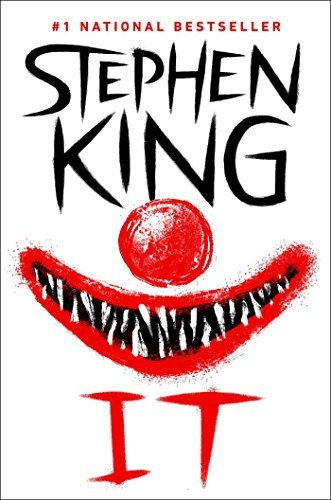

Review: Stephen King’s “It”

by Miles Raymer

Despite liking a few of his stories over the years and enjoying his memoir On Writing, I’ve been a snob about Stephen King for pretty much my whole adult life. I saw him as a literary shock-jock who attracted millions of readers by appealing to the lowest common denominator. But when I decided to make It my reading project over Thanksgiving break, I got to experience one of the great joys of being a lifelong learner: realizing I was wrong. Apparently I mistook King’s popularity for superficiality, not realizing how much emotional intelligence and narrative craftsmanship underlie his best work. It isn’t just a great horror story, or a better-than-average novel cranked out by an ultra-prolific author, or a 1,200-page doorstopper that somehow doesn’t feel overlong. It is all of those things, but it’s also a beautiful celebration of childhood friendships counterbalanced by a sobering meditation on the nature of adulthood and aging.

It takes place in the fictional town of Derry, Maine. Half of the story focuses on seven preteen misfits who form deep bonds of friendship over the course of one summer vacation in 1958. Their common enemy is the eponymous “It,” a shapeshifting monster that preys on children and frequently appears as Pennywise the Dancing Clown, though it also manifests as whatever a child fears most. The other half of the book follows the same characters as adults in 1985, 27 years later. They are scattered around the world, but one member of the group calls the others home when it becomes clear that It has re-emerged and is terrorizing the children of Derry once again.

From a structural standpoint, King includes an excellent conceit that imbues the novel with a sense of urgency. Adults who leave Derry gradually forget the traumatic and supernatural events of their childhood, so the characters begin to remember fragments from 1958 as they return home and encounter the places and people of their pasts. Rather than toggling between timelines in a rigid pattern, King braids the two eras together so that scenes in 1985 often trigger memories from 1958, giving the novel a dreamlike, echoing quality. This inverts the classic “return” stage of the hero’s journey: the characters don’t come home as wise, worldly adults bringing lessons from their adventures, but instead undergo a painful process of memory recovery and regression in order to rediscover the unique modes of courage and imagination that only children possess.

The town of Derry is King’s dark playground for exploring the timeless question of why evil exists and how it persists. The metaphor works not only because King has a knack for crafting creepy, atmospheric scenes, but because he understands that his monster represents everything humans work tirelessly to keep at bay: misfortune, anomie, decay, betrayal, death. Derry seems infected by It, becoming a kind of psychic accomplice whose residents unconsciously ignore or enable violence over the generations. The emotional gut-punch of an innocent child heading outside to play and never coming home reminds us that life is fragile and fleeting, and that disaster can strike even in our most mundane moments.

Readers interested in this novel should beware of its challenging and uncompromising content. To put it bluntly, this novel is supremely fucked up in several different ways. It’s terrifying, hyperviolent, overly sexualized, and weird, weird, weird. King uses harsh language and slurs that were common in the mid-to-late 20th century but may offend 21st-century readers. I actually think this is one of the novel’s strengths, both because it feels authentic to the eras being depicted and because it captures how much American culture has changed over time. The sexual aspects of the novel are probably the most controversial and likely to generate strong reactions, particularly one infamous scene. I have mixed feelings about how King deploys sexual energy and imagery. I appreciate King’s honesty about how preadolescent boys begin to think about girls and examine their bodies, but there are also moments when the focus on sexuality feels gratuitous. In the end I came to accept that––like many other aspects of It––the sex stuff is there to first pique my curiosity, then coax me to the edge of my comfort zone, and finally drag me over the line. It’s not lost on me that this is precisely the method that It employs to stalk and murder its victims.

Despite its grim tone and many horrific events, It is a hopeful novel that celebrates the power of human connection and bravery. There are many moments where characters find meaningful support, understanding, and love with each other, and these moments form the basis of their ability to confront and ultimately defeat It. Their unity carries both emotional and mystical force, reminding us that the bonds forged in childhood can possess a rare, incandescent strength. The protagonists generate oases of humanistic light that are all the more profound when contrasted by the desert of darkness in which they arise. Blurring the line between genre fiction and great literature, King delivers a powerful tale about the relationship between childhood and adulthood––one that honors what time takes from us and what it can never erase.

As usual, it’s a joy to read your review of a book I’ve loved. I’m glad we’ve gotten to talk about it too, and I plan to reread It sometime soon–it’s been years. As we talked about, the elements of sexuality are weird but they ring true to a certain part of adolescence and the balance of identity and the supernatural. I’m rereading Carrie and that’s a powerful theme in that book as well.

I have always felt that King GETS people in a particular and striking way. And in some of the interesting ways that fiction informs life, his writing has influenced me in deep ways. He has written about how his wife has helped him write his female characters, but still it seems remarkable to me how well done they are. And with the work I do I wonder how he understands prison dynamics so well, particularly in The Green Mile.

Anyway, thanks for writing this! Always a pleasure to return to words and dirt.

Thanks Katie for reading and leaving this lovely comment! I am so grateful for your readership all these years. 🙂